Issue Date: May 2, 2003

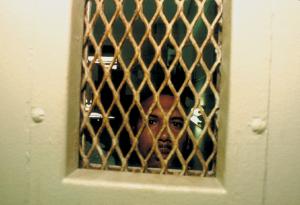

LOCKED UP Activists mark 30 years of struggle to reform criminal justice system in face of prison expansion By PATRICIA LEFEVERE Thirty years is not a life sentence. But for 30 years Charles and Pauline Sullivan have devoted their days to reforming the criminal justice system, in Texas and across the nation. The couple founded Texas CURE -- Citizens United for the Rehabilitation of Errants -- in 1972. The movement that began with organizing bus and van rides to Texas prisons so that indigent friends and family of inmates could visit their loved ones returned to the city of its origin in mid-October to mark its 30th anniversary. Scores of prison reformers from some 20 states where local CURE chapters have been initiated joined the Sullivans for tamales, tributes and an assessment of the tasks ahead. According to U.S. Department of Justice statistics, nearly 6.6 million people were on probation, in jail or prison or on parole in 2001. That number represents 3.1 percent of all U.S. residents, or one in every 32 adults. Included are 3,692 inmates on death row. The 100 or so reformers on hand in San Antonio had not overturned the death penalty, though several have worked to do just that. Claudia Whitman, an artist and member of Colorado CURE, produced “Reasonable Doubts: Is the U.S. Executing Innocent People?” a grassroots investigation project of the Quixote Center in Hyattsville, Md. In investigating more than 200 capital cases, Whitman said she has never found a case that did not exhibit some kind of prosecutorial misconduct and/or ineffective assistance by lawyers. She now trains family members of accused murderers and other interested parties to investigate capital cases. Moratoriums in Illinois and Maryland, pending moratorium legislation in eight other states and recent Supreme Court rulings against executing the mentally ill gave CURE members cause to cheer in a campaign that abolitionists expect to win incrementally, state by state, rather than with a broad stroke. Many who spoke at the four-day conference, held at the San Antonio State School, made reference to a “prison-industrial complex” that has reached across the nation in the last two decades. National and state legislators have used the threat of crime to justify building nearly 1,000 new jails and prisons since 1980. More and more communities have been persuaded that penal institutions provide jobs and boost the local economy. But the cost of maintaining these facilities is estimated at $40 billion annually -- $109.5 million per day. Although the United States has less than 5 percent of the world’s population, it incarcerates a quarter of the world’s prisoners. The cost of the 2.2 million people who work in the criminal justice system, including police, prison and court personnel, ran to $147 billion in 1999 -- four times the $36 billion spent in 1982. Are taxpayers getting their money’s worth? The reformers cited a rise in prison construction throughout the 1990s at a time when the crime rate was falling steadily. Increased penalties for nonviolent drug offenses have resulted in more convictions and more time for drug abusers. But a shortage of treatment programs has meant that many leave jail without the resources to stop their addiction. Locking nonviolent offenders with violent predators has led to harassment, beatings and rape, said the reformers. What is needed, they said, are treatment and education programs instead of jail. That’s an argument taxpayers are starting to understand now that as many as 600,000 inmates are being released yearly, most returning to their old communities with no rehabilitation or job skills.

Effie Bowers, founder of Arkansas CURE, pointed to a number of legislative issues being drafted in the Little Rock state house as well as other recently passed measures that she said would have a “devastating effect” on future generations. Bowers said lawmakers ought to refocus their energies from “chaining to training.” Her son at 17 committed robbery using a starter pistol, and “did the crime and deserved to do the time.” But Bowers said that after 10 years in prison he left “a very angry man with an adult body but no mental or emotional development,” because he received no counseling. ‘Messages from Mom’

Carolyn LeCroy became an activist after picking up an issue of the national CURE newsletter while incarcerated at the Virginia Correctional Center for Women. LeCroy received a 55-year sentence, suspended to six, for possession of marijuana that police found in her storage locker, but which she said did not belong to her. “I knew nothing about prisons, but I saw a host of women’s issues that needed to be addressed,” said LeCroy, who served 14 months. Since being freed, she has lent her skills as a film producer to those still inside. Each year at Mother’s Day and Christmas, she visits women’s prisons and spends up to 15 minutes with each prisoner videotaping a message to their children. The “Messages from Mom” project has won favor not only with inmates and their families, many too poor or living too far away to visit their mothers, but also with correctional officials. The prisons allow two women to help the inmates with their hair and makeup. For the Mother’s Day video, the institution provides a corsage. “Kids have lots of fears about their mom being away. In the video they see and hear that Mom is OK. The videos are something they can keep forever,” LeCroy said. “And women on death row are never going home.” The project, which began in one facility in 1999, now includes six prisons. LeCroy and her crew tape up to 65 videos per day, working 12 days in April and in early December. Donations cover the $10 cost per video. In the videos, mothers tell their children how much they love them. They regret not having been a good mother; they cry, sing, pray and thank their children’s caretaker -- often the mother of the prisoner. A prison psychologist told LeCroy that in many cases the video marks the first time a prisoner ever apologized and owned her crime. “I’m here. Prison saved my life,” and strong anti-drug warnings are among the “Messages from Mom,” she said. Women in Transition, a group founded by LeCroy 20 years ago and staffed by volunteers, provides parenting and other classes for inmates and ex-offenders. One of the myths about prisoners is that they enjoy three meals a day while watching cable television in air-conditioned cells. The reality is as stark as the difference between good grub and slop, in the view of many former felons and their families. Sun on the cinder block Lois Robison knows prison conditions well, as her son spent 17 years on Texas’ death row before his execution in January 2000 (NCR, Feb. 4, 2000). For 20 years Lois and her husband, Ken, have worked on behalf of prisoners and their families. Most recently Lois headed an effort that secured 638 new fans for indigent prisoners. Temperatures in some of the concrete and cinder- block jail buildings in Texas rise above 100 degrees and are the cause of death of several inmates each summer, Robison said. It is also a security issue, she noted. Guards stay holed up in their air-cooled areas and do fewer patrols of cellblocks. Six hundred and some fans hardly create a breeze among Texas’ 146,000 inmates, held in 105 facilities. Only six medical and psychiatric facilities are air-conditioned. The project has gained the backing of the Fort Worth diocese and of many Catholic and Protestant churches across Texas. It has also unleashed over 1,500 letters from grateful prisoners, even those who didn’t get a fan. “Inmates expressed surprise that anyone on the outside cares about their welfare,” said Robison, who with her volunteers is trying to answer all letters. Kathy Gess of Baton Rouge, La., writes 30 to 60 letters each month to prisoners across the nation. She is a lifetime volunteer who ministers to prisoners along with her husband, Tom, a retired chemical engineer. The couple is often seen in the Louisiana state house testifying on a range of prison issues or attending pardon and parole board hearings. They sponsor groups for the 3,600 men who are serving life sentences at the Angola, La., men’s penitentiary and at the women’s correctional facility. The couple helped initiate a children’s play corner at Dixon, Ill., Correctional Institute for visiting children of inmates. They also screen candidates for a transitional shelter for men. The Gesses, who won Catholic Charities’ USA 2002 Volunteer of the Year Award, are currently collaborating with Catholic Community Services of Baton Rouge to provide a resource book for newly released prisoners. The pair is also working with the agency to educate the public on the U.S. bishops’ recent pastoral on crime and criminal justice.

The Catholic church has been “deeply supportive” of the work of Ohio CURE, said Paula Eyre of Dayton. Eyre received a three-year grant from the Cincinnati archdiocese, which has helped her plan rallies, publish a newsletter and rent a booth at the Ohio State Fair for the past four years. The booth, which has drawn hundreds of visitors, featured a traveling exhibit sponsored by Murder Victims Families for Reconciliation. Such efforts also helped the 500-member Ohio CURE procure a $35,000 grant from the Catholic Campaign for Human Development. The money has gone toward opening an office and underwriting community justice cabinets -- round-table talks about restorative justice with people from the community and the Department of Corrections. Jeanette Popp, who chairs the Texas Moratorium Network, related her long battle to get Josef Marino’s death sentence commuted to life in prison without possibility of parole. Marino raped and murdered Popp’s daughter in 1988. “I don’t seek his life; I seek his discomfort in prison. I don’t want him to play basketball or swim, but I don’t want him treated like an animal either,” she said. Revenge vs. reform To counter a system in which “revenge is more powerful than reform,” Popp urged her audience to elect legislators, county commissioners and city councilors who favor prison reform and rehabilitation for inmates. “Texas has no rehabilitation facilities. Karla Faye Tucker rehabilitated herself, but they killed her anyway,” Popp said. She said she is considering running for state senator in 2004. CURE cofounder Charlie Sullivan thanked his audience for their outreach to the most outcast and vulnerable. A former priest from Alabama, Sullivan has done a lot of lobbying over 17 years while “eating my grits” in the Senate cafeteria. He pointed out the following “reasons for hope” in Congress and state legislatures: the movement to slow down the death penalty; measures to return Pell (education) Grants to inmates; funding for mentoring programs for incarcerated youth; and federal aid to states for violent offenders when they are released. But Sullivan cited areas still requiring attention. Among them the equalizing of sentences in the federal and state prison systems so that inmates serve the same time for the same crime. He called for greater funding for and recruitment of youth correction officers and more rehabilitation at the local and county level before prisoners are sent up to state penitentiaries. He also urged restoring voting rights to citizens with felony convictions. Only Maine and Vermont do not prevent convicted felons from voting. Thirteen states bar ex-felons from voting for life. Prisons are becoming the fastest growing nursing homes in the nation and the number of rapes and the spread of HIV/AIDS and hepatitis have pushed prison health care onto some legislators’ agendas. As the Sullivans -- now in their 60s -- contemplate their eventual retirement, they hope a fund can be set up “so we can pass something on to the new leaders.” The couple rents a small apartment in a tough section of Washington, bikes to thrift shops and appointments and to CURE’s office. The $40,000 per year operation is run from a corner in the upper eaves of the Jesuits’ St. Aloysius Church on North Capitol Street. Lawyer James Hamm of Tempe, Ariz., compared the pair to Sisyphus: Like the mythic Greek figure, the reformers have pushed an enormous boulder steadily uphill in the face of public opinion and lawmakers trying to roll it back down. Related Web sites

Patricia Lefevere is an NCR special report writer. National Catholic Reporter, May 2, 2003 |