Issue Date: May 23, 2003

Second in a series By LILI LeGARDEUR “Prisons are full of people with great potential. It’s sad that so many are not allowed to cultivate it, but are just discarded like toxic waste.” -- Tommy Silverstein, Leavenworth Prison, quoted in North Coast Xpress April/May 1996 The miniature carousel has inch-long sea horses in lieu of painted horses, one dangling from each arm of the bright green octopus draped over the carousel’s roof. The composition exhibits an engaged sense of play, a love of color and an exact attention to detail. But the medium is not clear. Is the small structure made of wood? Pipe cleaners? Some type of clay? “Toilet paper,” said Carol Strick, the Florida-based artist who was curator for this show of prisoner art at Critical Resistance South in New Orleans. “He takes toilet paper and mixes it with Elmer’s glue to make it like clay.” She demonstrates with her hands how the artist, a Michigan inmate named Robert Richardson, rolled paper and glue between his palms to make the thin, toothpick-like elements of the carousel walls. The central column of the structure, she points out, is the painted cardboard tube from a roll of paper towel. Small sticks frame a secret drawer that slides out from the octagonal base. This prisoner had access to paint. Some of them don’t.

The gallery show, titled “Art from the Inside Out,” was part of Critical Resistance South, a regional meeting that drew more than 2,000 critics of the prison industrial complex to New Orleans April 4-6. More than 40 inmate artists contributed drawings, paintings, sculptures, jewelry and folk constructions like Richardson’s carousel to the show. Inmate artists from across the South were invited, but Strick contends that packages from several southern prisons were interfered with, some never reaching their destination. Artists from Florida, Kentucky, Tennessee, South Carolina, Virginia, Louisiana and Georgia were represented, but most of the entries came from outside the 12-state southern region that was the focus of the conference. The two days of Critical Resistance South revolved around the alarming numbers and inequities of the U.S. criminal justice system. The information aired at the conference wasn’t new, but the numbers presented in context of this region were staggering. As revealed in “Deep Impact: Quantifying the Impact of Prison Expansion in the South,” a report by the Justice Policy Institute released at the start of the conference, 800 of every 100,000 people in Louisiana and 728 of every 100,000 people in Mississippi are in prison. (See chart below.) If both states were independent countries, they would lead every other country in the world in rates of incarceration. This dubious leadership in terms of imprisonment extends across the South, with the region as a whole accounting for 45 percent of the people added to U.S. prisons and jails between 1983 and 2001. In 2001, the South’s prison and jail populations represented one out of 11 prisoners in the world. Across the region, blacks were imprisoned at more than four times the rate of whites. Beyond all the statistics, however, what drew people to Critical Resistance South was the same conviction that Carol Strick brought to her art show: namely, that those caught up in the U.S criminal justice system are human beings worthy of respect. “So many people don’t even think of prisoners as people, as human beings with families and skills and lives,” said Melissa Burch, executive director of Critical Resistance South, who helped organize the conference. “Lots of people see prisoners as an aberration. But a show like this humanizes people about the issue, makes them open up to all the things that follow -- that the system isn’t fair, that it targets people.” Strategy sessions and workshops at the conference tackled such macropolitical issues as the role of mandatory drug sentences in driving up prison populations, the tie between poor schools and arrests in African-American neighborhoods and the profits that corporations derive from the current prison business. Here at a neighborhood gallery loaned by the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, though, the protest against the parallel universe of prisons was implicit. “This is about changing the public’s misconception of prisoners,” said Strick. “People are brainwashed as to what they can and cannot do. Supporting prisoners -- that’s bad, they can’t do it. But supporting art -- that’s good. You can do that.”

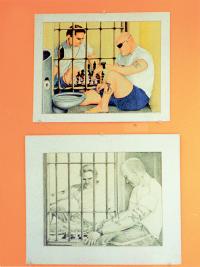

Walking through the New Orleans gallery, it’s easy to see that Strick’s tactic works. A delicately rendered acrylic and a related pencil drawing by Florida prisoner Bill Gregory show burly, tattooed inmates playing a game of chess through the bars that separate them. Nearby sits an actual chess set whose abstract pieces were carved from soap. Political cartoons by Texas prisoner Ana Lucia Gelabert poke jagged fun at “Mean King W” Bush, at U.S. consumption of resources and at the World Trade Organization. Across the room, a beautiful still life of roses floats high on the wall, making an observer forget for a minute that the artist, Arturo Restrepo, couldn’t possibly have painted it from actual roses. Strick didn’t start out with the idea of showing prisoner art when she began corresponding with inmates in 1990. She was simply looking for someone to write to after the death of her husband, whose experience as a prisoner decades before had sensitized her to the suffering of those incarcerated. Response to her ad for prison pen pals put her in contact with inmates Robert Knott and Harold Thompson. Knott, an artist, began enclosing drawings in his letters. It was the politically astute Thompson, though, who pushed Strick to explore the demimonde of prison life by reading alternative magazines online. One of those zines, North Coast Xpress, changed Strick’s life in 1995 when its editors asked her to investigate the case of federal inmate Loretta Goines. Goines had attempted suicide at Mariana Federal prison in Florida, and North Coast Xpress asked Strick to investigate rumors that she was being tortured. Strick arrived at the prison to learn that Goines had been chained to a concrete slab for 23 days. Her report on the incident was the first of what would become a regular column on prisoner abuse for the magazine, which is now called Justice Xpress. Strick still writes her column, “News from the Gulags.” Since staging her first prison art show on Manhattan’s Lower East Side in 1998, she also receives a steady flow of submissions from imprisoned artists, many of whom know about her through her writing. Five years later, she has staged seven prisoner shows across the country. Those exhibitions include shows at the Art League of Houston and at the Northern Westchester Center for the Arts in tony Mount Kisco, N.Y. Some of the art is for sale, though Strick insists that’s not the point. She doesn’t take commissions, and apart from an occasional donation of stamps from prisoners, her work is a strictly not-for-profit way of raising awareness. The more Strick talks about her artists, the harder it is to separate the beauty of their work from the harsh conditions of prison. Three necklaces by an anonymous artist turn out to have been made with bits of melted-down disposable razors. A finely shaded pencil drawing of a Mayan family by artist Javier Raygosa was done on a manila envelope -- the only paper he could get hold of in “ad seg,” or solitary confinement. Both he and Frank Fernandez, another brilliant draftsman whose Mayan studies and portraits of basketball stars stud the room, have been in isolation at California’s Pelican Bay Penitentiary for years. Bill Gregory lost art supplies he had accumulated over 12 years. Prison guards destroyed them. More than six months have passed, says Strick, and Gregory’s warden hasn’t decided whether to allow the artist to keep any new materials he might obtain. Most prisons sell rudimentary art supplies, she said, but they’re expensive -- and if art supplies are sold at the prison canteen, they can’t be shipped in. “Federal prisons generally offer better supplies than state prisons,” said Strick, glancing up at the acrylic on canvas by Raygosa. Many prisoners aren’t technically allowed to sell what they make, so she keeps a complicated set of accounts. The money from Raygosa’s sales, for instance, goes to his mother. LaSalle McDaniel, on the other hand, needs a pair of sneakers. If the drawings he sent sell at the show, Strick will buy a pair and send them to him. Those who are allowed to make money from sales receive it in the form of donations to their individual prisoner trust fund, where it can be used to purchase goods from the prison store and cover medical and dental costs -- all arguably inputs into the for-profit side of keeping prisoners.

Selling, however, can also be an insidious tool for changing attitudes. Strick recalls selling several pieces of Gelabert’s political work at a show in Westchester County, N.Y. “They’re the investors in the prison industrial complex up there,” said Strick. “That’s where you’ll find a lot of investors in Corrections Corporation of America.” Some of those investors may not be able to deal with the person behind the art they buy or the charge that put them in prison, she said. But for a few hours, before thinking catches up to them, those collectors have a relationship with an individual caught in a system where he or she may function as a profit-generating number in the investor’s stock portfolio. “The art gives people a moment of contact with a human being,” said Strick. “For the moment, you are absorbed in the art and are freed from the stigmas you came in with. It gives you a temporary respite from your life.” Visitors to the shows sometimes ask for the names and addresses of prisoners that Strick knows, realistically, they will never write to. The effect lasts about three or four hours, she said. “Then the impulse is gone because the fear sets in.” Lili LeGardeur writes from New Orleans. Next: Restorative justice looks at alternatives to the prison system and the industrial complex that profits from it.

National Catholic Reporter, May 23, 2003 |