Issue Date: May 30, 2003

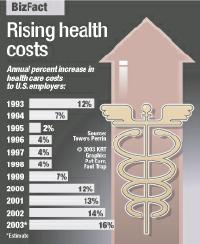

WEEK ONE By ARTHUR JONES The United States has two health care crises -- plus the finest medicine in the world for those who can afford it. The first crisis haunts the 41 million Americans who have no medical coverage at all. This, in the words of the Robert Wood Johnston Foundation’s Stuart Schear, is a five-part crisis. During a recent Cover the Uninsured Week conference, Schear described the crisis as “a health issue, an issue of economics, a political issue -- but also a moral issue and ethical issue.” The second U.S. health care crisis threatens those who do have coverage. It has two parts. Those Americans covered by Medicaid and Medicare are in publicly funded systems threatened by a political ideology that would drastically alter the current system in favor of privatization. In the other major covered group are Americans with private health care insurance. They, and their employers, are reeling from rapidly rising premiums. Richard Land, president of the Southern Baptists’ Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, reports that in his office premiums increased 31 percent in the past year, “and we’re supposedly fairly healthy since we’re nonsmokers and nondrinkers.”

Driving the rising costs are the insurance companies’ and investor-owned health care systems’ needs for ever higher profits. Add to the pressure to raise costs -- exacerbated by expensive new medical technology and highly touted new pharmaceuticals -- the consumer’s own expectations that the individual has a right to demand the best of everything that is out there. The health care debate, such as it now is, has become, like health care itself, increasingly ad hoc. That may change momentarily in the run-up to the 2004 presidential elections. Both President Bush and the Democratic contenders will use health care promises to attract voters. National health care advocates, however, want far more than piecemeal blandishments. The nation’s goal, said Catholic Health Association president Fr. Michael Place, “must be to reposition health care from its status as an important but optional building block to one that is essential for a free society.” Revisiting how far the United States has come in a half-century of health care provision improvements explains today’s gains, expectations and shortfalls. It reveals in stark relief the uninsureds’ plight. Understanding how U.S. health care arrived at this point can perhaps provide some direction for the future. NCR interviewed four authorities in an attempt to illustrate through the recent past the current complexities and the possible future.

Campaign for nation’s health In 1945, he said, President Harry Truman sought to mobilize the nation’s wealth and power to wage war against infirmity as it had successfully waged World War II. In a message to Congress three months after war’s end, Truman said, “We should resolve now that the health of this nation is a national concern; that financial barriers in the way of attaining health shall be removed; that the health of all its citizens deserves the help of all the nation.”

Twenty years later, said Olinger, President Lyndon Johnson traveled to Independence, Mo., to sign the bill that created Medicare. With Harry Truman at his side, Johnson stated: “No longer will older Americans be denied the healing miracle of modern medicine. No longer will illness crush and destroy the savings that they have so carefully put away over a lifetime so that they might enjoy dignity in their later years. No longer will young families see their own incomes, and their own hopes, eaten away simply because they are carrying out their deep moral obligations to their parents, and to their uncles and their aunts.” In 1972, Olinger continued, President Richard Nixon expanded Medicare to provide benefits to individuals with physical or cognitive disabilities. And in subsequent years, Medicare has grown to provide new services to the elderly and disabled. Looking at the push to privatize Social Security and -- within the context of President George Bush’s Jan. 29 State of the Union Address -- revamp Medicaid by delivering it to the states as block grants, Olinger, a Democrat, provided a historical example and a Republican rebuttal: In 1953, stockbroker Edward F. Hutton railed against the tyranny of Social Security. Olinger said President Dwight D. Eisenhower answered him that “it would appear logical to build upon the system that has been in effect for almost 20 years rather than embark upon the radical course of turning it upside down and running the very real danger that we would end up with no system at all.” UCLA’s Tabbush explains the past 40 years’ evolution in health care coverage for the average employee. Coverage has evolved and come almost full circle since the early 1960s, he said. Then, there was a fee-for-service, indemnity-style insurance, said Tabbush. “It was essentially a cost-plus system whereby providers received reimbursement based on the value of the activity they conducted. It was tailor-made for cost explosion -- the more providers did, the greater their income. The patient had no reason to restrain that activity. “Over time,” he said, “we evolved into a managed care environment where increasingly we moved from fee-for-service to fee-for-something-else. The most stringent form of managed care was fee-per-patient, which means the providers received a stipulated sum of money for every patient. “Under that system, the less they did the more money they made,” Tabbush said. In between, in this evolutionary chain, he continued, there was the Medicare intervention of the late 1960s that paid hospitals for inpatient services based on diagnosis. “So they had every incentive to diagnose,” he said. Then came the move to “capitation,” with the physician paid a fixed sum per patient. “Starting three or four years ago,” said Tabbush, “we had a backlash because cost-containment measures curtail demand and limit services, resulting in gatekeeping and access difficulties. Access was being made difficult while demand for access was exploding by virtue of increased technological breakthroughs [driven by] the Internet and direct consumer advertising.” Patients were demanding more, he said, “but supply was stymied by providers. Ultimately the system gave way -- the patients became not so much disenchanted as incensed with the system. That put pressure on employers. Now we’re moving toward significant degrees of choice.” As a result of employees’ demands for choice, the employers are being hit, he said. At the same time, said Tabbush, insurers want to get out of the business of managing demand (rather than manage risk, which is what insurance does). “They don’t want the negative publicity of being in a position of denying access. They don’t want legislatures around the country ganging up on them. They want to provide health benefits the employers are prepared to pay for, ideally a fee-for-service.” Choices facing doctors and patients Meanwhile, he summarized, evidence of the future is in the present: Providers will have to tell consumers that if they want something, they’ll have to pay for it. “That already is happening with tiered formularies.” Doctors and nurse practitioners now offer patients the prescription drug options between the cheaper generic drug and the brand name. “A lot of this is good,” said Tabbush, “because a lot of cost-unconscious decisions were being made because the bills were being sent elsewhere. When the patient himself has to bear a significant share of the cost burden, he becomes more collaborative.”

Which leads to Tabbush’s decade-ahead projection. “At the end of the day the people best able to make choices on what care to provide are the physicians. They have the best knowledge. Right now patients are making decisions. It sounds wonderful. But there are so many choices patients are unable -- and will always be unable -- to make due to lack of knowledge. “I think consumer choice works well, except in this market where there is an enormous asymmetry of information, and consumers really don’t know how to make the right choices. We’re going to have to devolve into a system whereby the experts make the choices, aligned with the patient’s interest,” Tabbush said. Georgetown’s Feder said that “to look at the evolution of the health insurance system is a good clue to why we don’t have a system that covers everybody.” Health insurance systems, she said, evolved from the 1950s as part of fringe benefits in employment, and grew through the 1970s in that form subsidized by a tax break that treats employer contributions to health insurance premiums as nontaxable to employees. There was an incentive to take benefits in insurance rather than in salary. “At same time there were efforts to enact a government program, attempts to cover everybody. Those failed. The focus shifted to the nonworking population -- medical care for the elderly, and added to that Medicaid, which focused primarily on pregnant women and kids. “Poor adults who are not parents of children are covered by Medicaid. But even if they are parents, the eligibility levels are so low that in most states earning the minimum wage is too high to be eligible,” she said. The result is a system in which most workers have coverage; in which those outside the workforce, the elderly and disabled are covered, but the poor working-age population (included in the 41 million uninsured figure) are not covered. “The structure,” she said, “leaves the population with least political clout outside the system.” Efforts to bring in this population, Feder explained, typically run into the need to disrupt coverage for those who already are covered through employment. Employed people become afraid they have more to lose than to gain. “It becomes difficult to establish a system that everyone is comfortable with,” she said. Further, she said -- and this confronts the ideological juggernaut of shrinking government -- “a system for everyone would require taking monies in through the tax system. What’s now paid for in other ways would be perceived differently if they were taken into taxes. “That, I believe, is how we came to be where we are. And why it’s so difficult to move forward,” she said. In the early 1990s, the first Clinton administration attempted to grapple with implementing a national health care plan that would provide universal coverage. Chris Jennings, today a health care consultant, was in the White House on the health care team at that time. He provides insights into the travails that hit the Clinton initiative. Jennings describes, too, the partisan political divide on the heath care issue, and analyzes the social and political divisions that hinder health care reform. In retrospect, explained Jennings, the Clinton administration may have had success in getting its health care plans considered and accepted “had President Clinton flipped his decisions. If he could have produced a welfare reform bill prior to health care reform, he might have produced a better health care reform bill and enhanced public receptivity to a government role in the oversight of health care. “The president had an ambitious agenda and was asking for a lot of hard votes from the Democrats [in Congress]: a deficit reduction package, trade bills, Haiti crisis. There was the so-called Travelgate, Whitewater, gays in the military, perceived gun control legislation, all used as political hammers to criticize Democrats in conservative districts.” Jennings said that, although the basis for the “so-called scandals were almost all ridiculous,” they nevertheless hurt the chances for the health care plan’s passage. “If you don’t have bipartisan support for it,” he said, “it becomes very vulnerable to unfair and fair criticism by well-funded interest groups who don’t want to see it happen.” Jennings said one could argue the Clinton plan -- in the face of a lot of political pressure aimed at undermining credibility and trust in the administration -- was overly ambitious. That situation, he said, “combined with the fact that the Republicans soon decided it was in their interests not to do anything on health care.” “It was also combined, frankly, with problems on our side,” said the former administration official, “in terms of marketing it. Internal squabbling was not helpful, we needed a unified administration working collaboratively to present a policy, broad support.” Today, he said, “Republicans in general fear enhanced or increased government involvement in health care because they think that may lead to more government control, which they believe is the ultimate negative. The Democrats fear, one, the current system getting worse, or, two, a [Republican-changed] system that will make the present system worse.” Jennings said it is not unusual in the United States for something as broad as health care to fall victim to failure -- “because this country is so non-homogeneous in its makeup and outlook: ideological, political and economic.” Therefore, he said, “if you cannot create a sustained vision that has relatively broad support, it is difficult to withstand the inevitable criticism posed by certain people who believe doing nothing is better than reforming the system.” Any administration determined on health care reform can begin from a partisan stance, he said, but needs either a leader totally trusted on the issue or an overwhelming mandate from the voters to carry it forward, and at least the veneer of bipartisan support to conclude it. Whatever structural reform is attempted on behalf of the 41 million uninsured, he said, also has to contain measures of medium or long-term benefit to people who do have health care. Though those who have it may believe today’s health care coverage substandard, he said, “it is the devil they know versus the devil they fear. And they won’t risk changing the system to embrace the 41 million unless it enhances affordability or increased protections for themselves. “That’s the challenge of health care reform.” The challenge for Catholics concerned for those excluded from coverage is the one presented by Feder: to be the voice in the structure that speaks for the population “with least political clout outside the system.” Arthur Jones is NCR editor at large. His e-mail address is arthurjones@attbi.com

National Catholic Reporter, May 30, 2003 |