Issue Date: July 4, 2003

For six seasons, grace was at work in HBO’s ‘Oz,’ the most Catholic show on television By RAYMOND A. SCHROTH The box cutter blade, dripping with blood, just thrust into the guts of a prison hospital patient judged better dead than sick, live and ready to talk. The stripped-naked young man, his pale flesh glowing in the glare of a single bulb, dumped like garbage on the floor of his solitary confinement cell. Bare buttocks, pumping. The unzipped fly. The hooded man jerking, bumping, writhing as the electric shocks zap his legs, arms and head in the last seconds of his life. The nude corpse of an old, fat priest who died soiling his underpants being gently washed by the convicted killer who had had shared his cell. I came late to “Oz” (Oswald State Correctional Facility), the HBO prison drama that closed its run this spring after 56 episodes in six seasons. I was like an inmate nabbed and sentenced for stealing some tires and tossed for three months and eight episodes into this special maximum security jail, ignorant of my fellow inmates’ lives from episodes 1 to 48. I knew nothing of the sins and crimes that had made enemies and built alliances among my fellows. Whom could I trust? How could I survive? Look for a protector? Talk to the chaplain? A New York Times writer speculated that the show’s popularity among women was due both to role reversals -- where tough women guards get to abuse vulnerable male prisoners -- and to fleeting full frontal male nudity. Or maybe the draw was simply its raw sensationalism. “Oz” (the first two seasons of which are now out on video and DVD) gave a documentary-paced peek into a forbidden world that lives by its own code that calls for perhaps one episode of oral sex, a male rape and three murders a night, and is not bogged down by the soap opera domestic drama that made “The Sopranos” the most talked about TV phenomenon among the chattering classes. I’d like to think it was something else. “Oz” was the most Christian -- the most Catholic -- show on television. My prison experience is limited but deeply felt. Thirty-five years ago, simply because I thought someone should see him, right after ordination I visited a Georgetown student accused of raping and murdering a little girl. It seemed the fellow had no concept of what he had done. During my 10 years at Loyola University in New Orleans, I was one of a team that said Sunday Mass in the city prison. A wonderful nun with a brief case full of rosaries and holy cards, a semi-blind black guitar player and I had roughly 25 minutes to enter a cell block still littered with breakfast trays, and get the men to turn off the TV and pray, do a few old Baptist hymns -- “Jesus on the Main Line, Tell Him What You Want” -- read a gospel, preach, pray, consecrate, communicate -- and get out. We gave Communion to everyone who came up. I suspect few were Catholics, but the gospel’s “I was in prison and you visited me” never made more sense. At least once that month or so, a sacrament had touched them and affirmed the dignity their environment denied. A few years ago, researching an article for Commonweal on Helen Prejean, I spent a day at the famous Louisiana State Prison in Angola, where the prison museum displays its original wooden electric chair with its big leather straps and sponges to transmit the current. “Oz” writer Tom Fontana seems to start with the premise that both his prisoners and their captors are human beings. Though his characters may break into groups -- administrators, guards, Irish, Latinos, Italians, Muslims, gays, the Alien Brotherhood, and others -- vice and virtue are evenly distributed. In each one-hour episode, edited into swift one- or two-minute scenes, inmates and administrators face moral dilemmas as crude as whether to kill a friend or as subtle as whether a long, ultimately destructive homosexual relationship may be really “love.” Each episode is narrated by a ghost, usually of an executed inmate who appears in a glass box, sometimes suspended in darkness, sometimes situated right in the rec room, sometimes accompanied by a cellist or surrounded by living characters, who, unlike us, do not know he is there. Perhaps because he is in heaven, he is very wise, and like a visiting angel, challenges us with questions about Justice Anthony Scalia’s pro-death-row Catholicism, and about forgiveness and the value of human life. A brutal woman guard who has routinely ordered prisoners to give her sex finds herself pregnant. But she is antiabortion. She will take a leave and have the child. Once in the New Orleans jail women’s wing, an inmate asked me to speak to her son. I’d try. Where was he? He’s downstairs in the same jail. It shook me to find mother and son both locked up within a few minutes of each other and unable to talk. But whole families, one way or another, inhabit “Oz.” Ryan O’Reily prepares his mentally ill brother, who killed someone in a fight, for the electric chair. Meanwhile their mother, a staff member, directs an inmate production of Macbeth -- during which an inmate prop manager will slip in a real knife for a battle scene, and an actor will be stabbed to death. Sheamus O’Reily, the miserable, rotten father, arrives as a fellow prisoner; his son, Cyril, at the governor’s direction and under his father’s signature, has undergone shock treatments to make him “sane” enough to die. Ryan shaves his brother’s head and kisses him goodbye. Seconds before the warden pulls the switch, the red phone rings. A reprieve. But a brief one. For the last time the O’Reilys process to the death house. The warden pulls the switch. The hooded body writhes and smokes. The warden pukes on the floor. Both the mayor and the governor are criminally corrupt. The mayor is jailed and a hired inmate slits his throat in his hospital bed. Even the warden dies -- as he staggers covered with blood into a party in his honor. A crazy Jewish fanatic, posing as a reporter, assassinates a Muslim leader, then, incarcerated, pleads with his black cellmate to kill him. Through all this blood, hate and squalor, grace is at work. A new librarian, suffering from breast cancer, believes that literature can transform -- or at least calm -- these violent men. When a young Hispanic sentenced for manslaughter is strapped naked in a restraining chair in solitary confinement, she bribes the guard to allow her to sit outside his cell and read him Tom Sawyer through the window in his door. The moral center of all this chaos is the psychologist nun, Sister Peter Marie Reimondo (Rita Moreno), who listens nonjudgmentally to all these sins and gently insinuates the alien thought that even in jail there is a God who loves. Sister, isn’t it right to try to survive, asks a distraught young man. Thank you, Sister. To survive, he performs oral sex and receives objects in the other end.

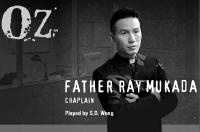

The young priest, Father Ray Makuda (B. D. Wong) declines to do an exorcism on a creepy, satanic death row inmate. The inmate accuses the priest of sexual abuse and the diocese removes him from ministry. We see Father Ray at his kneeler. When the death row inmates are posing for a commercial photographer, another inmate kills the priest’s accuser in a shower of sparks by shoving a hot photo lamp down his throat. Restored to ministry, Father Ray tells Sister Peter that he prayed his enemy would die. Unlike anything supposedly religious on TV -- like Sunday Evangelical preachers, Mother Angelica’s Masses and harangues, or stories about angels -- “Oz” has been about men and women, all too aware of their sinfulness, grasping for a touch of redemption. Ryan O’Reily shares his cell with the old Irish priest sentenced for civil disobedience. The priest, who has been trying to teach Ryan to overcome his bitterness and see the good in himself, drops dead defecating in his shorts. Ryan remembers the gospel scene where the women take Jesus from the cross and prepare him for burial. He asks permission to wash the priest’s body. Amen. Jesuit Father Raymond A. Schroth is community professor of humanities at St. Peter’s College in Jersey City, N.J. His e-mail address is raymondschroth@aol.com National Catholic Reporter, July 4, 2003 |