Issue Date: Posted July 30, 2003

Expanded article By TERESA MALCOLM It takes just one day to upend a parish that was built over 20 years: That was the lesson members of Holy Spirit Catholic Parish said they learned June 18. That was the day the new pastor, Fr. Ruben Delgado, arrived with officials of the Brownsville diocese and a stack of letters. Four were handed out to the employees who were at the Holy Spirit office. They were letters of termination. Witnesses said they believed that the rest of the letters were intended for the entire staff, but that the arrival of media and outraged parishioners cut short the firings. Meanwhile, they said, Delgado slipped into his office and was not seen again. A week later, he had resigned, never having said Mass in the parish, or indeed, parishioners said, shown his face after that Wednesday morning. But the “staff restructuring,” as he called it in a written statement released by the diocese, remained in place. It was the start of an ongoing battle in the heavily Catholic, Hispanic community of the Rio Grande Valley, fueled by the widespread belief that Delgado was merely the hatchet man for Bishop Raymundo Peña, 69, who many think ordered the firings in retaliation for the unionization of the parish staff last year. While the diocese maintains that the firings were Delgado’s decision alone, correspondence from diocesan officials indicated a pattern of moves against parishes with unionized staff, with workers fired at another parish and others threatened with loss of funding. The dispute in McAllen reflects a recurring conflict in the Catholic church when its strong support for workers’ right to organize clashes with its treatment of its own employees. “It’s unfortunate that many of our religious institutions -- not just Catholic -- often respond poorly when workers choose to organize,” said Kim Bobo, executive director of the Chicago-based National Interfaith Committee for Worker Justice. “Somehow they take it that the workers are opposed to the institution, that they don’t respect the leadership. In reality, workers just want to have a collective voice to affect their future.” In a situation such as McAllen’s, she told NCR, it is “such a marked contrast with teachings that support the right to organize, that this is met with harsh retaliation.”

While the United Farmworkers Union pursued a legal remedy on behalf of the four fired women -- pastoral associate Anne Cass, coordinator of family ministry/director of religious education Martha Sanchez, sacristan Rosario “Chayo” Vaello, and secretary Edna Cantú -- parishioners have carried out their own protest. From the first gathering of some 300 persons that Wednesday evening, and for the next three weeks parish leaders organized Communion services in the church’s courtyard. Meanwhile, the Valley press has acted as forum for spirited debate, with Peña coming under fierce criticism from local priests and lay people, while others have come to his defense, lobbing charges of disobedience and unorthodoxy at Holy Spirit Parish. The dispute has its roots in the unionization of four parishes in the Brownsville diocese last year (NCR, July 19, 2002). In addition to Holy Spirit, union contracts were signed at St. Joseph the Worker in McAllen, St. Joseph the Worker in San Carlos, and Sacred Heart in Hidalgo.

Fr. Jerry Frank, 61, at that time pastor of Holy Spirit, said he agreed to sign the union contract because of his concern over the diocese’s “insensitive, callous approach to lay employees.” He told NCR that since Peña came to Brownsville in 1995, diocesan employees had lost their jobs or were moved around. “They went through people fast,” he said. “It just seemed to be constant transition and flux, from what I could see. And the quality of the programs deteriorated, from a pastoral perspective.” He said he also noticed a pattern of priests moving to a new parish and dismissing the whole staff. “This didn’t seem fair and just to people who had worked for years and years for the church.” Another point of contention was Peña’s decision to change the lay employees’ pension fund to a 403(b) plan, which some employees felt shortchanged long-time and low-wage workers and provided a one-time check in early 2002 rather than monthly checks upon retirement. When his staff approached him to say they would like to join the United Farmworkers Union, Frank said he signed the contract willingly, “not knowing whether I had the legal right -- I was somewhat doubtful about that -- but as the only protest I could make, the only way I could ensure that my workers would get protected into the future,” he told NCR. He never heard from the bishop that he was not allowed to enter the contract, he said, which he took as tacit acceptance. Loss of funds threatened However, Frank said the three other parishes, less affluent than Holy Spirit, were threatened by the chancery with loss of subsidies. In two letters obtained by NCR, diocesan officials told Fr. Michael Seifert that his parish, San Felipe de Jesús Parish in Brownsville, would not receive funds from a grant from the Catholic Church Extension Society because the staff there was unionized. “[The] bishop approved the [Parish Needs Committee’s] recommendation that no funds be awarded while the parish is affiliated with the United Farmworkers Union,” wrote the vicar general, Fr. Robert Maher, April 7. “Because it is the expressed desire of the Catholic Extension not to be affiliated with parishes that formed this union, I trust you will understand our inability to help at this time.” A second letter, dated April 28 from diocesan development director Jesse Salinas, repeated the assertion that the Catholic Church Extension Society did not want to fund parishes associated with the union, citing the organization’s vice president, Richard Ritter. In a telephone interview with NCR, Ritter flatly denied that any such condition had been imposed. “We never told them or anybody that we would not help parishes because employees belong to unions,” he said. “We help parishes that the bishop asks help for and approves the grants for. To say we don’t help unions, that’s crazy. The record of the church is pretty straight on that, I think.” Salinas also told Seifert, “I am certain that if your employees knew of the ineffectiveness of the union contract with regard to their continued employment past your tenure there, they would not have signed. Did you not inform them that the entire unionized staff at Sacred Heart Parish in Hidalgo was let go and along with them, their union contracts? What did the union do for those employees?” Diocesan spokeswoman Brenda Riojas acknowledged that letters were sent to some unionized parishes by the vicar general stating that they would not be granted funds. However, she said, as soon as the bishop learned of it, the order was rescinded. “The parishes will be granted assistance from the diocese as well as from the Extension Society,” she told NCR. Early in 2003, Frank learned that he was to be transferred. That February, Peña came to Holy Spirit for a pastoral evaluation. “He talked to all the committees, all the staff, everybody,” Frank said. “And there’s no way that anybody that did such an evaluation could not come to the conclusion that this was an extraordinarily well-established, effective, spiritually-based, strong, vibrant, involved parish.” Parish that never sleeps A booklet for the parish lists 101 ministries, including ones that reach beyond the diocese to support for an orphanage for girls in Reynosa, Mexico, and a sister parish relationship with a church in Guajoyo, El Salvador. Frank and Holy Spirit parishioners have been at the forefront of political activities as well through the community organization Valley Interfaith. “I call us the parish that never sleeps,” said parish council chair Dora Saavedra. “Our staff puts in their 40 hours, but then they put in a lot of volunteer hours also. We’re known for social justice issues. We have gotten a lot of things done legislatively, adopted families at Christmas, helping out with whatever needs to be done.” Numerous parishioners recalled how following the evaluation, Peña praised Holy Spirit during a homily at the church, calling it a “true Vatican II parish.” He told them that he wanted Frank to replicate elsewhere what he had done at Holy Spirit. Frank balked at the bishop singling him out. “So I stood up after the homily -- I would have felt ashamed not to, or very self-centered -- and said, ‘Bishop, I’ve got to tell you that when I came to Holy Spirit 10 years ago, I came to a Vatican II parish. All I’ve been doing for the last 10 years is tagging along.’ The people then gave a big ovation to our entire staff -- the bishop heard that.” Frank said Peña assured him that he had no desire to remove the staff and undo the parish programs, but added that it would be the decision of the next pastor who came in. Delgado was appointed to Holy Spirit. The two priests had a two and a half hour conversation shortly before the transition. “I had no inkling that he was about to fire the entire staff,” Frank said. “I told him why I signed the contract. I told him my fears of the bishop’s possible vendetta against the staff for entering into a union contract. I told him it was a great staff and they’d done a wonderful job.” But Delgado declined to meet with the staff. “I felt like he avoided us,” said Cass, who works with family ministry and religious education. “How could you come to a parish and not meet with the staff?” After the meeting, Frank assured them that everything was going to be fine, said Vaello, who has been a parishioner since Holy Spirit was founded in 1981. But she said her fears were not easily assuaged. “The Monday before that Wednesday, Fr. Jerry was packing his stuff to move, and I said, ‘Fr. Jerry, are you going to stand with us when we get fired Wednesday?’ ... I don’t know why, I just had this real gut feeling that we were going to get fired.” Wednesday morning, Cantú was the first to arrive. The secretary had been through this before: She lost her unionized job in September 2002 as a secretary/bookkeeper at Sacred Heart Parish, where she is a parishioner, after a new priest came in July. Holy Spirit hired her part-time in October 2002 and full-time in March. On June 18 when Delgado walked in, followed by “all his committee,” Cantú said, “as soon as I saw them I knew what was going to happen.” When Cass arrived, one of the diocesan employees came to her office to ask where the rest of the staff was. Most were on vacation, Cass replied. The woman handed her an envelope from the stack Cass said she held. The letter inside said her “services to Holy Spirit Church are no longer required.” Cass had worked for Holy Spirit for 22 years, including five and a half as pastoral administrator when the parish was without a priest. Cantú’s husband was at the office to take his wife, several months pregnant, to the doctor because she wasn’t feeling well. They left when Vaello showed up and offered to cover the front desk. “I didn’t know all these people had come in until I started seeing people going back and forth, and I thought, ‘OK, this is really it,’ ” Vaello said. “This woman comes in and asks me who I am, and I tell her. She smiles and says, ‘I have something for you!’ like it was this wonderful surprise. I knew what it was immediately.” Vaello read her letter of termination, and called her husband and told him to call the local media. “I was pretty calm,” she said. “I think I was in shock.” What hurt her most, she said, was when she realized they were changing the locks to the church. “The idea that they couldn’t just simply ask us for the keys -- that they thought we were going to do God knows what.” Cantú received her letter of termination when she got back from the doctor. The diocesan official who gave her the letter told her she could reapply for her own job. Cass called Rebecca Flores, their union representative, who called the press. Soon volunteers who were present started calling parishioners, who started “coming in droves, just irate,” Cass said. Once the news media arrived, she said, diocesan staff quit giving out envelopes. Parishioner Harry Mosher was one of the volunteers who came that afternoon. His uncle, Fr. Gus Pacheco, was Holy Spirit’s first pastor. “I’ve witnessed over the years every transition of one pastor to another,” he said. “This is the first time in the history of this parish in my experience to have witnessed such a hostile takeover. It was done without feeling, it was done without professionalism, it was done without the sense of Christianity about it.” Mosher recalled Peña’s words of praise for Holy Spirit back in February and noted that the fired women “were the leading factor in bringing us to practice what Vatican II really wanted the church to look like. The bishop commended us for that, and then he turns around and commits an act like this. It almost feels like he wanted to split us up -- because I think Bishop Peña is intimidated by Vatican II.”

Sanchez, meanwhile, was worried about preparing for a group of children’s first reconciliation that night, and after reading her letter, she tried to see Delgado. She was headed off by a diocesan official who asked what she wanted. Sanchez said she needed to know when the termination was effective. They told her, “Right now,” she said: “You need to get your things and you need to leave.” So Sanchez gathered her materials for the sacrament that night and handed it to a diocesan staff member, saying, “Everything is ready.” She called a few people who lived close by to help her pack, and soon the office was full of volunteers. “From there, I just started packing and the media started coming. It was just like -- are we in a dream? We started hearing the sounds of the locks being changed. They’re changing the locks on us. This is 4 or 5 o’clock and we haven’t eaten anything. We don’t even know how the hours went by so fast. It was unreal.” By late afternoon, two security guards arrived. According to Riojas, Delgado hired them for the evening meeting that parishioners had organized. “With reactions being what they were, it was better as a precautionary step to have security on hand,” she said. Locks and security guards were a shock to a parish accustomed to open doors, Vaello told NCR a week and a half after the firings. “You walk into our parish and everybody would always say, ‘It’s such an alive parish,’ people always coming and going. The only time we close is for lunch” -- she slipped into the present tense -- “then we keep one side door open. The sign says, ‘Closed for lunch,’ but people just go to the side door and come in.” Delgado: ‘I’m sorry’ Frank received the call from Cass who told him about the firings. He asked to be transferred to Delgado. “I asked him about three times: ‘How could you let the bishop use you like this?’ Then I asked him, ‘How can you lift up your face and look people in the eye on Sunday, knowing all the destruction of people’s lives and careers that you’ve brought in this parish?’ Well, he never did show up for Mass.” Frank said that all Delgado replied was “ ‘I’m sorry’ -- but I don’t know what he meant. I’m sorry you misunderstood? I’m sorry you don’t see it the way I see it? I’m sorry for what I did? I said, ‘It’s nice that you’re sorry but it sure isn’t going to undo the damage done.’ ” After he got off the phone with Delgado, Frank said he cried for two hours, “beside myself with incredulity and sadness and anger at what I knew the bishop had done.” The presence of diocesan personnel that day, he said, as well as the assignment of a deacon to Holy Spirit shows the bishop’s hand in the events. “Priests don’t change deacons, bishops change deacons,” Frank said. Riojas told NCR that although it is not customary procedure to have diocesan personnel present at such a change, they are available if the priest requests assistance. Delgado made such a request to the diocese’s human resources department, she said. “I think he anticipated there might be some resistance to the changes he was planning.” The deacon, Alvin H. Gerbermann, was appointed to work during the transition at Delgado’s request, she said, and is not permanently assigned to the parish. Frank, who is temporarily assigned to a group of five rural missions in La Joya, said that when he arrives at a new parish, “I never fire people. I give people time to show me what they’re worth, what they can do. I have a basic presumption that my predecessor was not a complete idiot.” Late afternoon on June 18, attorneys filed a temporary restraining order calling for the women to keep their jobs on the grounds that they were let go without due process. But it had to be served to Delgado, and by then he could not be found, Cass said. By Friday, with the priest still unreachable, the diocesan attorney, David Garza, agreed to accept the restraining order. The women reported to work, but were soon told that they were on paid administrative leave, and had to vacate the premises. The church had a weekend full of events coming up -- baptism classes, vacation Bible school, two weddings, a quinceañera -- and a vanished pastor. “I felt responsible” for them, Cass said. “It’s not right to bring the parishioners into this mess, especially when they’re celebrating the most important events of their lives with the church. We’re willing to stay here and help, but we’re being told that we have to leave.” Vacation Bible school was canceled. One bride was first told that a deacon would perform the wedding ceremony, but eventually a priest -- not Delgado -- was found to fill in, Cass said. “We still don’t know what [Delgado] looks like,” said parishioner Chuck Stewart. “We wouldn’t know him if we saw him on the street.”

Delgado was heard from in the form of a brief statement released through the diocese June 18. He wrote, “Before coming to Holy Spirit Parish, I had an opportunity to carefully review and study the payroll roster and the job descriptions that are in place. I found that some job descriptions for existing positions included activities that are normally undertaken by volunteer lay ministers.” He said that he was restructuring “the 31 paid positions ... including combining of positions, position eliminations and the addition of religious personnel.” According to Frank, Holy Spirit employed nine full time parish workers, plus the staff of the nursery school, which functions separately, as a parish elementary school would. “If you want to throw that in, of course you can come up with 31 people, because you need people to run it. They’ve got a staff of their own,” he said. Mosher, a member of the parish’s finance committee, disputed the implication that Holy Spirit could not afford to pay its workers. “We had a healthy balance in our account, and all positions were budgeted for,” he said. “And the budget we have is a very conservative budget -- enough to make sure that our programs work well and were effective. People were paid appropriately, a living wage.” “It’s angering when he says the jobs should be done by volunteers,” said Adam Moya, president of Holy Spirit’s high school youth group. “We have hundreds of volunteers. Pretty much everybody at church volunteers in one way or another. But we still need those four people there. They’re the masterminds behind all the volunteering. If the volunteers didn’t have them, we’d all be running in circles.” Temporary transition team In any case, parishioners questioned if finances were the issue, why two people had been hired by Delgado in what looked like the same positions as those held by the women. Riojas said that the two new employees, the deacon and a secretary, are part of a temporary support team for the transition chosen by Delgado. Meanwhile, Holy Spirit parishioners had rallied. More than 300 people assembled for a hastily called meeting and protest that first Wednesday night. Members of various committees coalesced into one Parish Leadership Committee to respond to the crisis. “We united in an amazing way,” said Dora Saavedra, parish council chair.

The leadership committee, together with the parish’s two permanent deacons, took the unusual step of organizing a separate Communion service, to be held in the church courtyard, concurrent with regular Mass times. Several anonymous priests provided consecrated bread, Saavedra said. As people arrived, they were told that a visiting priest would be saying Mass, but were given the option of attending an outside service in support of the four employees. McAllen’s newspaper, The Monitor, reported that the numbers outside “dwarfed” the few dozen in attendance at each Mass the first Sunday, June 22. The Mass collection, usually totaling about $13,000, dropped down to just short of $3,500. The collection taken up outside to go toward the women’s legal fees came to $7,000. That Sunday a letter from the bishop to Holy Spirit parishioners was inserted in the bulletin. “I am deeply hurt by the dishonesty in the statements that were made about me and about your new pastor,” he wrote. He said that he had given no instructions to Delgado. The hiring of staff fell under a priest’s ordinary jurisdiction in canon law, and as such he would not countermand Delgado’s actions, Peña said. He wrote that the downsizing was “made in the spirit of the Second Vatican Council ... to motivate and offer all the parishioners the opportunity to share in the mission of the church.” As for Delgado’s absence, Peña said, “He was profoundly hurt by the verbal and physical abuse he received. Because of this, I have asked him to take some time off.” A number of parishioners wondered how Delgado could have been physically abused when no one had seen him. When NCR asked the diocese to elaborate on the accusation, spokeswoman Riojas said, “Fr. Delgado had been approached by some individuals who shouted in his face, and he feared that these emotions could escalate.” The bishop’s letter did little to dispel the belief that he was behind the firings. “The bishop talks about how the parish has violated [Delgado’s] rights and his person,” Frank said. “If anybody’s violated that poor guy, it’s the bishop who used him to do his dirty work.” Cass said that even accepting that the bishop had nothing to do with Delgado’s actions, she would like to ask him: “Does he approve of what Fr. Ruben [Delgado] did and does he hold up as a model for the business world getting rid of employees the way Fr. Ruben did? Because the bishop himself said the way we do this as a parish should be a model for the marketplace. Why wouldn’t he be upset about it? Why does he keep going behind canon law and saying in canon law the pastor can do what he wants?” Debate erupted in the local press. Frank and several other priests strongly criticized Peña in the press, while Valley Catholics weighed in not only on the firings, but also the choice of the parishioners to hold separate services. Several letters to The Monitor were from people who said they were former Holy Spirit parishioners, accusing the parish of “straying away from authentic Catholic teaching,” in the words of one writer. Holy Spirit parishioners found themselves defending their liturgical practices while trying to steer the conversation back to the issue of justice for the workers. On June 26, Peña held another news conference to announce Delgado’s resignation, which he called “Holy Spirit Parish’s great loss. To help him recover his energy and tranquility, I have granted him a period of extended rest until he receives a new assignment.” Peña said that Delgado’s personnel decisions would remain in place. He appointed a temporary parish administrator for Holy Spirit, Jesuit Fr. Brian Van Hove, spiritual director at the St. Joseph and St. Peter Seminary.

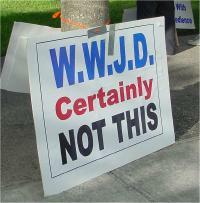

Separate services were held the two following Sundays. The protesters were at pains to explain that they did not want to cause division in the parish over the choice to go inside to Mass or stay outside and attend the Communion service. “We’re trying to do this as respectfully and as lovingly as we can,” parishioner Roland Quintanilla said at the end of the outdoor Spanish service June 29. “Everybody is given an option to protest in whichever way you can. Ask God, ‘What do you want me to do?’ because that’s the bottom line.” One parishioner who chose to go inside, Marisa P. Scott, told NCR, “I believe what the women were working for was a united church and honestly it hurts me to see us divided.” She said she felt “shock ... like someone had told me someone very close to me had died” when she heard about the firings, but “if there’s a priest, I’ll go to Mass inside.” Scott was also filling in as a cantor in the choir’s absence. “In my heart I feel it’s counterproductive,” she said of the outside services. “I think that by all of us participating in the sacrifice of the Mass and sharing the Eucharist as one that we will become more empowered by receiving Christ together.” Peña took aim at Holy Spirit in another press release June 30, in which he said the separate services reflect the parishioners’ misunderstanding of eucharistic theology. “The real issue is not the action taken by the new pastor,” he wrote. “The real issue is the church’s theology on priesthood and the Eucharist. This same group has picketed the ordination of our diocesan priests the last two years. On June 22, they were hurriedly removing the women’s ordination signs from their banners and replacing them with union signs.” Peña described his meeting with the parish council in February and said, “I was advised by one of the members that they did not need a pastor; they could run the parish themselves.”

Frank came to Holy Spirit’s defense in an open letter to Peña, saying he received support as pastor from staff and parishioners alike. “I recall that person from the parish council telling you that they did remarkably well running the parish at a time in the past when no full-time pastor was available to them because of the shortage of priests,” he wrote. “The record indicates that in fact they did very well. Such deserves recognition rather than dissembling and misrepresenting the person’s words to you.” He continued, “I am so proud of them! They are expressing the tough love and courage that our church needs from its laity in these troubled times.” Workers reinstated The third Sunday of separate services came July 6. The next day, the four workers and Holy Spirit parishioners achieved a small victory when the four women were temporarily reinstated for at least two weeks, pending mediation. A hearing had been scheduled for July 8, and the bishop, Delgado and several other priests had been called to testify, according to James Harrington, director of the Austin-based Texas Civil Rights Project, which is representing Cass and Cantú. The hearing was postponed when the diocese agreed to mediation. “I think this whole problem is going to turn on whether the bishop wants reconciliation or not,” Harrington told NCR. “He’s certainly going to set the tone, and so far it has not been very good. He’s been very combative in the press,” although Harrington noted a more conciliatory tone from Peña when mediation was announced. Harrington, a Catholic, said he saw in the conflict “a Vatican II quandary. There’s a parish council, an active parish, running into the arbitrary power of the bishop, and I think both have a hard time dealing with each other.” Riojas said that in the wake of the events at Holy Spirit, the Brownsville diocese will be examining the process of what happens when a priest goes into a new parish and deals with existing staff, a study that may result in specific guidelines and policies. Meanwhile, the four women returned to work July 7. Cass said it was “stressful,” especially with the two new employees of Delgado’s transitional team. “We don’t know what their responsibilities are, we don’t know what ours are,” she said. “Our primary focus still is to make sure the ministries, the way people are accustomed to them happening, continue,” Cass said. Following the announcement, Saavedra said, the parish leadership team decided to go back into the church, after having three Sundays of services outside. “We’ve asked parishioners not to wear their red shirts in order to make a good faith effort at mediation,” she added. “We realize this is a temporary solution and it is a first step toward what we hope will be a reconciliation through correcting the injustices that have occurred,” she said. “The best way to describe our reaction is cautiously and hopefully optimistic.” “We’re not going to allow them to destroy all the hard work and everything that’s been built,” Vaello had told NCR earlier. “I don’t know if we’ll ever be the parish that we were, but hopefully we’ll be a stronger parish. Where it will end, only God knows, but one thing is for sure: Because of my belonging to this parish, all the things I’ve learned there from people like Anne [Cass] and Martha [Sanchez], I’ve learned to trust people, I’ve learned to trust my instincts and I’ve learned to trust in God. It’s just really sad that the hierarchy, the people who should be our shepherds, those are the people we’re losing trust in.” Teresa Malcolm is an NCR staff writer/reporter. Her e-mail address is tmalcolm@natcath.org National Catholic Reporter, posted July 30, 2003 |