Issue Date: September 5, 2003

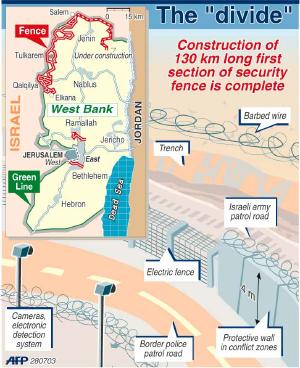

Israel’s ‘separation fence’ sabotages the road map to regional peace By PAUL JEFFREY The road to peace in the Middle East runs into a wall just outside Shareef Omar Khaled’s village. For years the 60-year-old farmer has ridden astride his slow-moving, rusting tractor down the stony path that leads from his village of Jayyous to the acres of olive, fig and walnut trees that feed his family. Yet in the last month a fence has blocked that road. There’s a gate in the fence, supposedly for use by village farmers who want to reach their fields, but the key is held by the Israeli military. In this land of brutal eye-for-an-eye violence, where everything bristles with political meaning, what word one uses to describe the barrier across Khaled’s farm road quickly reveals allegiance in the conflict. Most Israelis call it “the separation fence” -- as in good fences make good neighbors -- and claim it is needed to protect them from suicide bombers like the one who blew up a Jerusalem bus Aug. 19, killing 20 people and wounding scores more. The Palestinians call it “the wall,” evoking memories of Berlin and claiming the structure represents a wholesale grab of fertile land and fresh water, creating facts on the ground that will leave any eventual Palestinian state with lots of people and no viable way to survive. Whether fence or wall, the project began as an initiative of those on the Israeli political center-left who wanted a way to slow the expansion of illegal settlements in the occupied West Bank. But the original idea was to place the fence on the Green Line, the de facto border between Israel and the occupied West Bank since the 1967 war. The fence would work both ways, keeping unwanted Palestinians out while also slowing the dismemberment of the West Bank by the settlements and settler-only roads that have carved the Palestinians’ land into pieces. Along with the curfews, roadblocks and humiliating security checkpoints imposed by the Israeli military, the measures have made travel in the West Bank difficult if not impossible. A zealous proponent of settlements, Ariel Sharon, Israel’s current prime minister, was at first opposed to the fence. From the perspective of Sharon and other Israelis, who since the creation of the Jewish state have seen borders as a temporary thing, nothing should stand in the way of “Greater Israel.” Yet as suicide bombers and the media collaborated to build public pressure for the fence, it occurred to Sharon that the barrier could serve the right’s interests if he located it not on the Green Line but inside the West Bank. With most of Israel’s center-left political forces in disarray following the violence of the second intifada that began in 2000, the right took power and got its wish, and the fence line now snakes in and out of the West Bank, enveloping fertile valleys and hilltop settlements. Proposed future extensions of the fence, including one separating off the Jordan Valley from the rocky highlands, will leave the Palestinians with dramatically less than they’ve bargained for. Fence becomes fiasco Sharon’s final solution of fence, settlements and bypass roads will leave the Palestinians endeavoring to form a viable state while living in three separated enclaves -- with little farmland or water -- occupying only about 42 percent of the West Bank. Forget about Palestinian Muslims and Christians living in East Jerusalem. “Annexed” (rather than occupied) in 1967, East Jerusalem will be fenced out of Palestine and into Israel, creating facts on the ground that preconfigure any final negotiations about the holy city’s fate. Yossi Alpher, an early proponent of the fence for security reasons, argues that the fence “has taken on the dimensions of a fiasco” since Sharon “hijacked” the project. An ex-Mossad agent and a former director of the Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies at Tel Aviv University, Alpher wrote in his Aug. 11 column on Bitterlemons.org: “Sharon intends to transform the fence from a security-separation barrier to a means of defining the enclave-like nature of that 50 percent or so of the West Bank that he intends to offer the Palestinians as a ‘state.’ ” The Palestinian Authority, plagued by inefficiency and corruption in the best of times, was slow on the uptake when construction on the barrier got underway a year ago. Villagers affected by the fence traveled to the rubble in Ramallah, where President Yasser Arafat holds court, to plead for help.

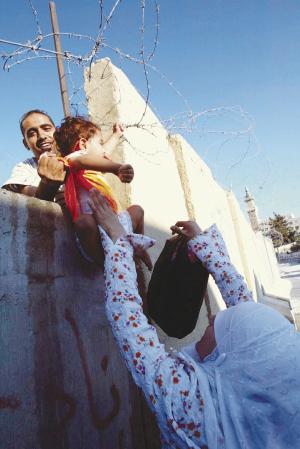

With what was to become the internationally sponsored “road map for peace” gaining momentum, however, Palestinian leaders were preoccupied with other matters. Yet under continued pressure from farmers like those in Jayyous, Palestinian diplomats made the rounds in Washington. State Department staffers and National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice, genuinely horrified at what the Israelis were attempting, convinced President George W. Bush to raise a fuss. The White House leaked a suggestion that the United States would cut back on Israel’s current aid package if the fence didn’t change course. But the election campaign had started, and Democrats courting Jewish and Christian Zionist voters jumped on the president for betraying Israel. Bush backed away from a hard line on the barrier, suggesting that the United States could just slap Israel’s hand by withholding $1 billion from a $9 billion loan guarantee package awarded -- on top of the $3 billion a year in military and other aid -- for faithful support of the U.S. invasion of Iraq. For Sharon, the diplomatic fuss was simply a temporary hassle he could afford to patiently endure, all the while quietly continuing to alter the facts on the ground. And then an Islamic militant dressed as an orthodox Jew did the prime minister a political favor by blowing himself up on a bus full of people, including children, coming home from praying at the Western Wall Aug. 19. A way to ‘steal land’ For Khaled and his neighbors, far from the diplomatic wars and urban terrorism, the barrier is simply a way for Israelis to steal their rich farmland. Not to mention their water. The community’s seven wells lie on the far side of the barrier, and Khaled says village families are already experiencing water shortages. So 32 Jayyous farmers spend most nights of the week camped out in tents in their fields near the far side of the barrier, accompanied at times by international peace activists. The farmers intend to stay there, especially through the critical olive harvest in October, to make sure the Israeli military doesn’t lock them out of their fields. They aren’t impressed with government promises that the gate built into the fence will always be usable. In late July the gate was being opened only one hour in the morning and one hour in the evening. “The gate only exists for the media, so the Israelis can say they let the Palestinians go through the gates to their fields. But it’s a lie. Elsewhere the settlers have put fences around Palestinian villages, around our farms, and they leave a gate that the farmers can use for six or seven months. After that they change the locks and the farmers can never touch their land again,” Khaled told NCR as he sat on his tractor near the barrier, eyeing an Israeli jeep idling beside the fence, its occupants closely watching. “If we farmers lose our farms we will be turned into beggars. That’s why we’ve moved to the tents. We’re determined to stay on our land. Even if the army tries to destroy us by force, we are ready to die, but not to live as beggars,” he said.

“If they really want a fence for security purposes, why didn’t they build it on the Green Line? It’s six kilometers from here. I’ll pay 50 percent of the cost if they build it there. Yet, to be honest, we don’t even want them to build it on the Green Line, because one day we hope to have peaceful and direct relations with the Israeli people. But the wall will block forever any chance of peace. Sharon and the right tell the Israeli people that the Palestinians are terrorists. We aren’t. We want peace. We want life. But they consider us animals to be fenced in,” Khaled said. According to Abdul-Latif Khaled, a university-trained hydrologist who lives in Jayyous, water has been a key to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict since the 1940s, and is key to the barrier’s design today. “When you look at a map of the natural resources of the West Bank, especially the water resources, and compare it with a map of the wall, you’ll see that they match. That’s not a coincidence. Sharon invited people from the army, the settlers and the resource managers to a meeting, and he gave them a blank sheet and told them to write their wishes. And then everyone wrote down what they wanted. That’s why I call it the wall of wishes. “The shape of the wall is determined by the wishes of the settlers, the resource managers and the army. Most of our fertile land and most of our water are on the other side. The wall will kill us. We tried to protest. We appealed to the courts, but all the community’s arguments were rejected. The courts won’t touch what they consider political or military decisions,” he told NCR.

Abdul-Latif Khaled says the barrier diminishes the chances for peace. “How can we talk about peace when we can’t talk to each other because there’s a wall between us? The first step toward solving the problems is to start talking to each other. But not with a barrier in between. We need to start removing the physical barriers if we’re ever going to get to the more difficult mentality barriers. We have no problems with the Israeli people. The problem is with their leaders who have convinced them that this is for their security. But you don’t create security taking the sustenance from our kids. …How can you talk about peace when such actions are just making inevitable another cycle of violence?” The Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, Michel Sabbah, the top Roman Catholic official in the region, is a fierce critic of the barrier. And he says the Israelis would do well to consider the effect it will have on their political culture. “The wall separates two peoples, but it doesn’t isolate the Palestinians, who have the whole world open before them. It isolates the Israelis, it puts them in a new ghetto. They are not here to be in a ghetto. They came here to live in this new world, open to the whole world, to be welcomed by the whole world, starting with the Palestinians. This wall will isolate the Israelis, put them in a big prison, separating them from the other peoples of the Middle East. The wall shouldn’t be built, and if it is built, it should be demolished as soon as possible,” Sabbah told NCR. Protection from bombers According to Linda Epstein, the director of the Israel office of the Jewish Federation/Jewish United Fund of Metropolitan Chicago, that’s not how most Israelis see the barrier. It’s about security, period. “The fence wasn’t put up after Israel won the ’67 war, but rather years later after the public started screaming at the government for protection from suicide bombers and shootings. The government finally acquiesced to public demand,” she told NCR. Muki Tsur, a former general secretary of the kibbutz movement in Israel, says the barrier has its roots in political strategies, but claims those strategies don’t interest the ordinary Israeli on a bus or in the mall who’s worried about being blown up by a Palestinian combatant with a bomb strapped to their chest. “Every politician wants to use the wall to support their political plans, yet public support for the wall comes not from analysis or political reflection, but from fear,” he told NCR.

Gadi Golan, the head of the Religious Affairs Bureau of the Israeli foreign ministry, says the fence is born of frustration. “We have the most powerful army in the Middle East, but when it comes to terrorism the army is of no use,” he told a visiting ecumenical delegation Aug. 14. He said the experience of fencing in the Gaza Strip (also occupied by Israel in 1967) had reduced terrorist attacks, and Israel now wanted to replicate the experience on the West Bank. He belittled the complaints of farmers who are losing their land to the barrier. “The land where the fence is built continues to belong to the farmers. It’s not expropriated. They’ll have trouble using it, that’s true, but it remains their property,” Golan said. According to Michael Tarazi, a legal adviser to the Palestinian Liberation Organization’s negotiating team, a wall in itself isn’t necessarily a bad idea. “When I first heard about the fence or barrier or whatever you want to call it, I thought, ‘Terrific, build a wall on the Green Line, I sort of like the idea. I don’t want to see your settlers and soldiers any more than you want to see the suicide bombers. We want our security too. So build the wall, and we’ll stay on our side and you’ll stay on your side.’ But of course they aren’t building the wall on the Green Line. They are building the wall inside the occupied Palestinian Territories in such a way as to take most of the land for the Israeli side while leaving most of the Palestinians on the other side. This is a forced immigration policy. Small villages are left without work, they’re cut off, and people leave. Israel then annexes what they call ‘abandoned villages.’ It’s all part of a great strategy to get rid of Christians and Muslims while taking as much of their land as possible,” Tarazi told NCR.

“The wall creates a Palestine that is simply not viable. You put a big cage around the population centers, which are much like Bantustans, you connect them with a few bridges and tunnels, and there you go, there’s your state. But it’s not viable. They are making it impossible to have a Palestinian state that will function,” he said. While analysts contemplate the ramifications of the barrier on the future of peace negotiations in the region, many of those directly affected by the structure are more worried about where they are going to grow their crops. For weeks, Katam Mahmod Zud watched the fence stretch across the fertile field below her house in the northern West Bank village of Ti’innik. Although she mourned what was happening to her neighbors, she was thankful she would be left untouched. And then one day Israeli surveyors left a brightly painted plastic marker between her house and the small field where she grows grains and beans for her family of 10. “They told me it was for the second phase of the wall, and that in a few months the construction crews would arrive to build another wall,” she told NCR. “Where am I then going to grow food for my children? The wall is taking the food out of their mouths.” Paul Jeffrey is a freelance writer who lives in Honduras. National Catholic Reporter, September 5, 2003 |