Issue Date: September 19, 2003

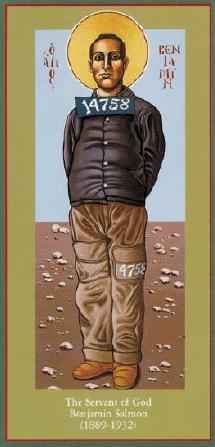

Once despised, now honored, Ben Salmon endured jail, force-feeding and public contempt for his convictions By MELISSA JONES The three Dominican nuns who were recently imprisoned for breaking into a missile site aren’t the first witnesses for peace to cause a sensation in Denver. In 1917, during “the war to end all wars,” labor activist Benjamin J. Salmon announced that he would not serve in the military. He was one of only four Catholics to resist military service during World War I. Salmon instantly became a target for contempt. Catholicism’s “just war” teaching has generally kept it from being considered a pacifist religion -- at least not in the same way as Quakers, the Church of the Brethren, and Mennonites have been considered. In 1917, there were no provisions for conscientious objectors of any kind, but members of the traditional “peace” churches could choose alternative service. Most Catholics were willing to serve in battle during World War I, in part because so many of them were immigrants who wanted to prove their patriotism. Salmon’s choices were military duty or prison. He chose prison. Salmon was born in Denver to a working class immigrant family in 1889. He was a devout Catholic who attended Mass and was proud of his Knights of Columbus membership -- until the Knights kicked him out for his pacifist views. Salmon refused combat service because he said the gospel forbade killing. He refused to cooperate with any aspect of World War I because he believed it was a “capitalist war.” He wrote, “If Christians would have the same faith in their God that the non-Christians have in a mere materialistic idea, ‘Thy kingdom come’ would shortly be a reality in this world of sorrow and travail.” He also wrote, “Countless millions of children will be underfed and underclothed and undereducated in the years to come in order that the debt of the recent hysteria [war] may be paid to the international bankers.” Salmon’s troubles began in December 1917, when he refused to fill out a questionnaire required for selective service processing. By January 1918 he was arrested, court-martialed and sentenced to death, a sentence that was later reduced to 25 years in prison. Military authorities eventually offered him noncombatant service, but Salmon had vowed total non-cooperation with the military and refused. He remained in prison, leaving his pregnant wife and dependent mother without support. During his prison time he was beaten and placed in solitary confinement. His treatment in prison led him to write, “The safest place for a man who refuses to fight is in the army.” Although U.S. soldiers began to return home after Armistice Day in November 1918, Salmon remained in prison. In June 1919, he began a hunger strike “for liberty or death.” He went without food and water for 13 days. Authorities then moved him to the prison infirmary and began to force-feed him milk by shoving a porcelain funnel down his throat. As he continued to refuse food, the government sent him to a hospital for the criminally insane. The milk diet and force-feeding weakened him to the point of death. Unwilling to be blamed for his demise in their hands, the government officials finally released Salmon in December 1920. He returned home to a strained marital life and ostracism from the Denver community. The family eventually moved to Chicago. The religious life in the Salmon home produced a priest, a Maryknoll nun working in Nicaragua, and a dedicated Catholic daughter who had 12 children. Ben’s son, Charles, is an ordained priest in the Denver diocese and a chaplain at the Gardens of St. Elizabeth retirement community. Charles remembers his father as being “a very charitable individual,” who showed kindness to relatives and neighbors. Charles admitted that his father occasionally became distracted with activist life and “sometimes he slighted his own family just a bit.” But he added, “I’m sure it was not on purpose. He had strong opinions and I believe he was sincere.” Because of his treatment in prison, Ben Salmon suffered from physical weakness and stomach ills that led to his early death Feb. 15, 1932. This was during the Great Depression and times were rough for the Salmon family. Charles said his mother’s father, a successful businessman, helped the family after that. Robert Ellsberg, author of All Saints: Daily Reflections on Saints, Prophets and Witnesses for Our Time (Crossroad, 1997), said he chose Salmon for his anthology because of “the incredible vilification he had to endure,” from the church, his neighbors and his family. Although some called him crazy and irresponsible, Ellsberg said Salmon was an incredible witness to the fact that “one’s ultimate obligation is to one’s own immortal soul.” Salmon had only an eighth-grade education, but he had an amazing grasp of moral issues. While imprisoned, he used a Bible and volume 15 of the Catholic Encyclopedia to write a remarkable 200-page manuscript opposing the just war theory. He could also be short and to the point, as he was known to proclaim: “There ain’t no such animal as a just war!” National Catholic Reporter, September 19, 2003 |