Issue Date: October 10, 2003

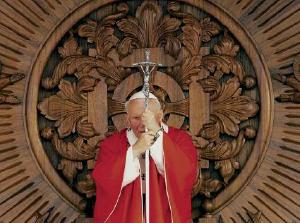

In his long, polarizing pontificate, John Paul II has defied categorization By JOHN L. ALLEN JR. Is John Paul II liberal of conservative? Is he pro- or anti-Western? Is he the liberator of the peoples behind the Iron Curtain, or someone many women regard as an obstacle to their emancipation? Is he the pope who gave away his episcopal ring in the Brazilian shantytown to express the church's solidarity with the poor, or the pope who broke the back of liberation theology? Is he the pope who apologized for Galileo and Jan Hus, or the pope who cracked down on Hans Küng and Charles Curran? Is he the pope who visited the Rome synagogue and the Western Wall, or the pope who beatified Pius IX? Is he the pope who gave the archbishop of Canterbury a gold pectoral cross, a symbol of episcopal authority, or is he the pope who approved a document elevating to quasi-infallible status the teaching that Anglican ordinations are invalid? The truth is that this pope is all of the above. No public figure of the 20th century, and perhaps few ever, defy easy categorization quite like Pope John Paul II. His pontificate marks its 25th anniversary Oct. 16, and over that quarter-century, John Paul has stood at the center of all of the most important religious, political and cultural tensions of his time. Biographer Jonathan Kwitny once called Karol Wojtyla the “man of the century,” not necessarily because he was the 20th century’s greatest man, but because all of the century’s historical dramas cut across his own life story. Perhaps it’s that complexity that makes John Paul’s worldview maddeningly difficult to pin down from the point of view of either partisan politics or the usual philosophical systems. Nietzsche once said that great men should be beyond good and evil, an option clearly not available to a pope. Yet there is a sense in which a pope has to be beyond the confines of strict logic, for the sake of keeping his massive worldwide community of faith in equilibrium. John XXIII once put the point this way: “I have to be pope both for those with their foot on the gas, and those with their foot on the brake.” On this rare milestone -- only two other popes have reigned 25 years, Leo XIII and Pius IX, both in the 19th century -- any attempt to spell out the significance and contributions of his pontificate from a single angle of vision is thus destined to be an exercise in selective perception. Instead, we’ll consider how his papacy looks from multiple points of view: Jews, theologians in Europe and North America, Arab Christians, educated Catholic women, Catholic social activists in Latin America, Catholics of the Eastern churches, traditionally minded Catholics, and moderate American bishops. As Einstein theorized about place and time, so too John Paul’s legacy is, in important respects, relative to where one stands. Jews As a Pole coming of age in the 1930s, Karol Wojtyla watched the Nazi assault against European Jewry unfold. He grew up in a mixed Christian-Jewish community in Wadowice, and his best friend was a young Jew named Jerzy Kluger. In just one among a thousand-and-one signs of John Paul’s special vicinity to Jews, he is the first pope ever to speak Yiddish. Polish Jews remember Archbishop Karol Wojtyla with fondness; during the pope’s 2002 trip to Poland, a leader of Krakow’s Jewish community described how Wojtyla had “reached out a blessing hand to us.”

That life experience has made him a historic force as far as Jewish relations are concerned. In 1986, John Paul became the first pope since the age of St. Peter to set foot inside a Jewish place of worship, visiting the Rome synagogue. In 2000, John Paul visited Jerusalem’s Western Wall, also known as the Wailing Wall for its sad Jewish history, leaving behind a handwritten note expressing regret for centuries of Christian anti-Semitism. “We are deeply saddened by the behavior of those who in the course of history have caused these children of yours to suffer and, asking your forgiveness, we wish to commit ourselves to genuine brotherhood with the people of the Covenant,” it read. The transformation in Jewish-Christian relations has played itself out in practical ways in dialogues, exchanges and joint service projects. The climate is sufficiently new that on Sept. 11, 2000, more than 150 rabbis and Jewish university professors signed a public statement called “Dabru Emet: A Jewish Statement on Christians and Christianity,” asserting that “it is time for Jews to learn about the efforts of Christians to honor Judaism.” Indeed, John Paul has been so consequential that influential Jewish leaders around the world are taking an unusual interest in the politics of the papal transition, worried that his successor will not have the same existential “feel” for Jewish-Christian relations. Not every American Jew, however, is quite so impressed. The decision to beatify Pius IX, the pope who kidnapped a Jewish child in Bologna and who put Rome’s Jews back in their ghetto, is one serious question mark. Another is John Paul’s decision not to respond when President Bashar al-Assad, in the course of welcoming the pope to Syria in May 2001, said that Jews had killed Christ and tried to kill Muhammad. Debate over the possible beatification of Pius XII, the canonization of Edith Stein, the implosion of a mixed commission of Jewish and Catholic scholars to deal with the Vatican archives, and lingering bitterness over a Carmelite convent at Auschwitz all cloud the relationship. There were also less significant disappointments, such as the choice to visit the Soviet-era memorial to all the victims of fascism at Babi Yar during the 2001 trip to Ukraine rather than the specifically Jewish monument a few hundred meters away. Moreover, the pope’s personal example has only gone so far, and perhaps could only go so far, in undoing ancient prejudices. This is true even within the Holy See, where the working assumption of an enmity between Jews and Christians is still alive in some quarters. This came into view during the American clergy sex abuse crisis, for example, when some Vatican officials quietly whispered that the attacks in the U.S. press represented the Jewish-dominated media’s payback for the church’s support of the Palestinians. Yet even granting these shadows, many Jews would probably concur with Rabbi Michael Kogan of Montclair University in New Jersey: “This pope is the best pope the Jews ever had,” Kogan told NCR. “Some Catholics may not like him, but as far as we’re concerned, he’s great. He is determined that the church will enter the 21st century free of anti-Semitism.” Theologians in Europe and North America Put three Catholic theologians in a room and you’ll have four opinions, so to pretend there is anything like a consensus view of John Paul’s pontificate would be nonsense. On the other hand, a survey of the theological community in Europe and North America would probably reveal majorities on the following points:

Whether these impressions are right or wrong, fair or unfair, is another matter, but they do represent what many professional Catholic theologians, teaching at Catholic institutions and understanding themselves as loyal to the church, think. Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the John Paul’s top doctrinal aide, has scoffed at suggestions of an oppressive climate within the church, observing that the actual number of theologians who have gone through his office’s full disciplinary process is low, perhaps as few as a baker’s dozen. But this overlooks the fact that many of these targets have been carefully chosen as symbols of whole trajectories in Catholic thought -- Charles Curran for sexual ethics, Leonardo Boff for liberation theology, Jacques Dupuis and Roger Haight for religious pluralism. Of course, not every Catholic theologian analyzes John Paul’s pontificate in these terms. Many are grateful to the pope for what they see as vigorous intellectual leadership, especially in well-received encyclicals such as Veritatis Splendor in 1993 and Fides et Ratio in 1998. Many would also agree with the essential argument of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith’s 1990 “Instruction on the Ecclesial Vocation of the Theologian,” that “the freedom proper to theological research is exercised within the church’s faith.” Perhaps what one can say about John Paul and theologians is that his determination to draw lines in the sand has cheered those who find themselves within the boundaries, and alienated many who feel the lines have been wrongly drawn. Arab Christians Of the world’s 1.5 billion Christians, only 14 million or so live across the Arab world, with the largest concentrations in Egypt, Lebanon and Iraq. Yet these Christian populations exercise a disproportionate hold on the imagination of the Christian world, because they are the caretakers of Christianity’s most holy sites, and because they cling tenaciously to an increasingly perilous future.

The clearest confirmation of the threat to Arab Christianity is the ongoing shrinkage of these communities, as growing numbers of frightened Christians pull up stakes and leave. Today more Christians born in Jerusalem live in Sydney, Australia, than in the city of their birth. More Christians from Beit Jala, a traditionally Christian town near Bethlehem, now reside in Belize in Central America than are left in Beit Jala itself. In Bethlehem, the city of Christ’s birth, the Christian population was reduced from a 60 percent majority in 1990 to a 20 percent minority in 2001, meaning some 23,000 persons left the region. In Iraq, the situation is similar. Some 200,000 Christians have left since the first Gulf War. At the start of 1991, the Catholic population of Baghdad was more than 500,000. Today, Catholics number about 175,000. “It’s like a biblical exodus,” one Vatican official told NCR last February. No attempt to understand the deep affection of most Arab Christians for John Paul II can ignore this reality. In fact, John Paul’s outreach to Jews has been matched almost pace-for-pace by his efforts with Muslims. He was not just the first pope to visit a synagogue, but also the first pope to enter a mosque, visiting the Grand Mosque of Omayyid in Damascus in May 2001. While he has pushed forward with Jewish-Christian dialogue, he has also met Muslims more than 60 times, including visits to majority Islamic nations such as Egypt, Syria and Morocco.

The same message that the pope is a friend of Islam was the subtext to John Paul’s stern moral opposition to the U.S.-led war in Iraq. Before fighting broke out, observers feared that Arab Christians would be targeted for anti-Western backlash. Yet in the most intense periods of the conflict, only a handful of such cases occurred. Most observers credit John Paul’s stance with the result, since it allowed the “Islamic street” to distinguish between the West, Christianity and the Bush administration. All these gestures have helped reassure Muslim public opinion that one can be both Arab and Christian, that the latter does not mean disloyalty to the former. Hence for Arab Christians, perhaps the force of John Paul’s personality has not been enough to reverse the long-term threats facing their community, but his outreach to Islam has at least made their situation more tenable. Educated Catholic Women Perhaps John Paul’s comparatively enlightened approach to women -- appointing women as his spokespersons at international conferences, opposing discrimination against women in public policy -- is the most one could reasonably expect from a Polish church leader of his generation and life experience. Measured against the expectations of many educated Catholic women, however, especially in the developed world, the pope has often seemed a disappointment. The sense of alienation can be profound. This includes some of the women who under other circumstances would be considered the church’s most loyal base of support. An anecdote about a disaster that almost was makes the point. When John Paul II visited Toronto in June 2002 for World Youth Day, he spent most of his nights at Morrow Park, in a motherhouse and retirement home for the Sisters of St. Joseph. The nuns had turned their facility upside down to accommodate the pope and his entourage. Many were aged and infirm, and one even asked her spiritual director if it would be selfish to ask God to keep her alive long enough to meet the pope. Plans called for the superior of the community to greet John Paul in brief remarks at lunch, while the other sisters would join the lunch in the refectory along with the Canadian bishops and members of the papal party. At the last minute, however, the nuns were told that they would not be taking part, and there would be no greeting. Local organizers scrambled to find out what had gone wrong, and eventually word came down from the pope’s inner circle that no religious woman was to speak. The reason was fear that the nuns might deliver some sort of feminist statement, reflecting the memory of Sr. Theresa Kane, an American Mercy nun who in October 1979 publicly pleaded in front of John Paul that all ministries of the church be open to women. In the end, the pope himself saved the day, agreeing immediately when an organizer asked whether he would like to meet the sisters. The point, however, is that the near miss illustrates the paranoia that can surround the “women’s issue” on John Paul’s watch. Flash points include the United Nations Conference on Population and Development in Cairo in 1994 and the World Women’s Conference in Beijing in 1995, both moments in which the Holy See challenged the agenda of international women’s groups. Other tensions include a battle throughout the 1990s concerning “inclusive language,” meaning non-gender-specific terminology in scriptural translations and liturgical texts, and the U.S. bishops’ lengthy effort to produce a pastoral letter on women, eventually scuttled in the wake of repeated Vatican interventions. Finally, the 1995 apostolic letter Ordinatio Sacerdotalis affirmed that the ban on women’s ordination is a matter of divine revelation. The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith later said that this teaching has been “set forth infallibly” by the magisterium. While John Paul has argued this teaching is about fidelity and not about power, and that women have separate rather than inferior roles to play in the church, that line of argument has been unconvincing to many Catholics who think the real concern is maintenance of patriarchy. The failure of John Paul to move significant numbers of women into positions that do not require ordination, such as Vatican leadership posts, reinforces this impression. Naturally, not every Catholic woman feels this way. Some believe the pope, with his doctrine of male-female complementarity, as well as his defense of life and of the family, coupled with his fierce devotion to the Virgin Mary, has pointed the way to a more authentic “new feminism.” Defenders also point out that the pope has appointed an unprecedented number of women to pontifical councils and academies. In 1988, John Paul even published an encyclical letter on the dignity of women titled Mulieris Dignitatem, which affirms the contemporary women’s movement as a positive “sign of the times,” though it also warns against the “masculinization” of women. At the end of the day, however, even the staunchest defenders of John Paul tend to acknowledge that the Catholic church has a problem with women. A bishops-sponsored survey of Australian Catholics in 1999 reached a conclusion that has parallels across much of the Catholic world, finding a widespread sense of “pain, alienation and often anger resulted from a strong sense of women’s marginalization, struggle, disenfranchisement, powerlessness, irrelevance and lack of acknowledgement in the church.” Whether the blame for this is to be placed on the pope, on aggressive feminism or some other combination of factors is in the eye of the beholder. Social Activists in Latin America John Paul has been a relentless critic of social injustice. Citations could be compounded almost indefinitely. In January 1999, for example, the pope issued his conclusion to the Synod for America, condemning “social sins” and the viciousness of neoliberalism. Italian historian Andrea Riccardi, founder of the Sant’Egidio community, recounts a July 22, 1979, conversation in which the pope expressed his own view of the deficiencies of capitalism: “Look, I can surely say by now that I’ve got the antibodies to communism inside me. But when I think of consumer society, with all its tragedies, I wonder which of the two systems is better.” John Paul’s relentless insistence on humanizing globalization has put the advocacy of social justice in the job description of church leaders. Under his guidance, a new generation of bishops has come of age across Latin America -- Cardinals Oscar Andrés Rodriguez Maradiaga in Honduras, Jorge Maria Bergoglio in Argentina and Cláudio Hummes in Brazil -- passionately committed to the struggle for justice.

At the same time, however, John Paul will forever be remembered in Latin America as the pope who gave a cold shoulder to Archbishop Oscar Romero of El Salvador and the pope who authorized a crackdown on liberation theologians such as Leonardo Boff, and who publicly upbraided Jesuit Fr. Ernesto Cardenal for his political commitment. Taken individually, each of these actions may be explicable given the circumstances and issues. Boff, for example, got into trouble not so much for his views on social matters as for his ecclesiology in the book Church, Charism and Power, which seemed to promote a kind of class struggle inside the church. Certainly few serious Christians could argue with Cardinal Dario Castrillón Hoyos, who said of the most extreme versions of liberation theology: “When I see a church with a machine gun, I cannot see the crucified Christ in that church.” Moreover, John Paul’s own attitude toward liberation theology was never wholly negative. In 1979, John Paul said he supported the idea of a theology of liberation, but that it should not be tied exclusively to Latin America or to the sociologically poor. He quoted theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar to the effect that a Catholic theology must have a “universal radius.” Later, he encouraged the drafting of a more positive document after the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith issued a harsh rebuke in 1984. The result, 1986’s “Instruction on Christian Freedom and Liberation,” for the first time in a magisterial document adopted the phrase “integral salvation” to describe the redemption won by Jesus Christ. In a letter to Brazil’s bishops in 1986, John Paul called liberation theology “not only opportune, but useful and necessary.” Collectively, however, the crackdown unleashed under John Paul created the impression that the Vatican had taken sides against Latin American Catholicism’s most distinctive attempt to apply the Second Vatican Council. Many Latin American social activists hence feel a deep ambivalence about John Paul. They approve much of his social teaching (while noting a certain incoherence between the fiercely anticapitalist Solicitudo Rei Socialis and the more ambiguous Centesimus Annus) and his pastoral instincts. Yet they also know that he’s the same pope who groomed Cardinal Alfonso López Trujillo of Colombia who made a personal crusade out of the assault on liberation theology. He has yet to advance the sainthood causes of any of the movement’s martyrs such as Romero, or the six Jesuits and their housekeeper and her daughter killed at the University of Central America in 1989, or the four American church women (Ita Ford, Dorothy Kazel, Jean Donovan and Maura Clark) killed in El Salvador in December 1980. Activists may thus see John Paul’s papacy as a glass half full, emphasizing his strong prophetic language and doctrinal progress, or as half empty, focusing on the disciplinary moves and his aversion to liberation theology’s heroes. Eastern Catholic Churches Arguably few Catholic communities in the 20th century suffered more for their fidelity than Eastern Catholics, whose churches were forcibly dissolved under the Soviets and whose clergy were generally given the option of becoming Orthodox priests or going to jail. The stories sometimes defy belief. One Greek Catholic priest in Ukraine was crucified upside down on a prison wall for his refusal to cut ties with Rome; another was boiled alive in a vat of oil.

This is the stuff of early Christian martyrologies, with the difference that these events happened just 50 years ago. There are 21 Eastern churches in communion with Rome, and typically they have two overarching preoccupations. The first is a worry that amid the massive worldwide Latin rite, their distinctive identity will be lost. The second is the question of relations with the Orthodox traditions out of which most emerged. On both points, John Paul II has been arguably the most sensitive pope in history. First, he has clearly made the preservation of Eastern traditions a priority of his pontificate, pushing through a new edition of the Code of Canon Law for Eastern Churches and calling repeatedly for Catholicism to “breathe with both lungs,” East and West. He has visited virtually every nation in which an Eastern Catholic church community is found, meeting with their leaders and elevating their social profile. In October 2001, John Paul approved a Vatican ruling that recognized the legitimacy of the eucharistic prayer used by the Assyrian Church of the East, the Orthodox companion to the Chaldean Catholic church, even though it lacks an institution narrative -- traditionally considered the essential element for valid eucharistic consecration. The ruling was considered stunning by many experts, and a further sign of the pope’s determination that Eastern rites and traditions be shown respect. Second, John Paul, the first Slavic pope, has engaged in a historic campaign of rapprochement with the Orthodox. He has a long list of breakthroughs to show for the effort, including a Christological agreement with Oriental Orthodox churches in 1994 declaring the old Monophysite controversies resolved, well-received trips to Greece, Romania, Georgia and Bulgaria, and high-level exchanges with all the hierarchies of the 15 autocephalous Orthodox churches. In 1995’s Ut Unum Sint (“That They May Be One”), John Paul offered to open a dialogue with the church’s ecumenical partners about how the papacy might be restructured, a gesture intended above all for the Orthodox, for whom the papacy is the single towering practical and theological obstacle to greater unity. During his May 2001 trip to Greece, John Paul offered an apology to the Orthodox that seemed to dispel centuries of bad blood.

Despite that, Catholic-Orthodox relations have frequently hit a brick wall. In mid-September, for example, Archbishop Jean-Louis Tauran, the Vatican’s foreign minister, traveled to Georgia to sign a bilateral agreement that was scuttled at the last minute due to strong opposition from Orthodox nationalists, marching under the banner of “Georgia Without the Vatican.” The Russian Orthodox church has for years denied John Paul his dream of a trip to Moscow, citing proselytism by Catholics in Russia and property disputes in western Ukraine. Despite these tensions, however, most Eastern Catholics regard John Paul as a hero. Jesuit Fr. Robert Taft, an American expert on the Eastern churches, said there’s no argument about the historical significance of John Paul’s papacy from his point of view. “On the issues I work on, he’s been one of the best popes we’ve ever had,” Taft said. “I understand why others might be more critical, but when it comes to my professional interests, he’s terrific.” Catholic Traditionalists Catholics who regret the abandonment of older liturgical practices, or who worry about the doctrinal solidity of post-Vatican II church teaching, find much to praise in John Paul II. They applaud the 1988 Ecclesia Dei indult that allowed the celebration of the pre-Vatican II Latin Mass with the permission of local bishops. They were heartened by the pope’s willingness to draw lines in the sand against what they saw as clearly excessive theological dissent. They support John Paul’s plain talk on issues of sexual morality, his capacity to denounce what he sees as a “culture of death.” At the same time, however, traditionalists also feel alienated from this pontificate in many important ways. On liturgical matters, for example, they charge that the pope may be a reverent celebrant himself who says Mass in Latin every morning, but that he has largely been content to let the post-Vatican II liturgical deconstruction unfold. He even appointed as his own master of ceremonies an Italian liturgist, Bishop Piero Marini, who was the private secretary of the man responsible for the conciliar liturgical reforms, Archbishop Annibale Bugnini. Moreover, while John Paul’s stands on abortion, birth control and gay rights have cheered traditionalists, his stance on some doctrinal questions has been far less reassuring. His decision to call leaders of the world religions to Assisi three times to pray for peace (1986, 1993 and 2002) created worries about relativism, or the idea that one religion is as good as another, and syncretism, a blending of elements of different religions into one New Age pâté.

In general, the pope’s ecumenical and interreligious outreach has led some traditionalists to charge him with “indifferentism,” treating truth and error as if they’re the same thing. This line of concern even led some conservative Catholics to criticize John Paul’s 1992 beatification of Opus Dei founder Josemaria Escriva, since Escriva allowed non-Catholics and even non-Christians to sign up as “collaborators” of Opus Dei. Italian writer Vittorio Messori coined a phrase to sum up this traditionalist critique of John Paul: “Strong on morals, but weak on faith.” Conservatives also sometimes grumble that John Paul has indulged his own personal intellectual tastes too much in magisterial documents, replacing the scholasticism derived from Thomas Aquinas with the a 20th century personalism that owes more to Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. John Paul’s style has always rubbed some traditionalists, including some in the Vatican, the wrong way: too much travel, too many saints, too many spectacles in St. Peter’s Square, too much face time on TV, too much emphasis on his personal devotion to Mary and previously obscure figures such as the Polish nun and visionary Faustina Kowalska. Finally, some traditionalists say the pope’s willingness to fight dissent has been far too episodic and inconsistent. Sure, Hans Küng lost his license to teach Catholic theology, but Fr. Richard McBrien is still happily ensconced at the University of Notre Dame, and with him a host of other liberal theologians. While the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith issues stern reminders on the ecclesial vocation of the theologian, bishops who challenge that position, such as German Cardinals Karl Lehmann, and Walter Kasper, even manage to become cardinals. A whole generation of church bureaucrats and pastoral workers remains in place despite indications of deep differences with at least certain elements of the Catechism of the Catholic Church. After 25 years of John Paul’s reign, therefore, traditional Catholics may admire the pope’s moral stands, but at the same time they fear that his doctrinal, philosophical and administrative leadership has been at best a mixed bag, and in some cases downright toxic. Moderate American Bishops Most bishops feel a tremendous admiration for John Paul II as a man of deep fidelity and obvious personal holiness. They watch him pour himself out in service, and cannot help but be moved. Moreover, they know the affection he awakens in people, especially the young, and the moral esteem in which he is held even outside the Catholic church. At the same time, many American bishops feel reservations about some aspects of John Paul’s pontificate, especially the way in which it seems to have operated at times on an adversarial model with respect to bishops and bishops’ conferences. The symbol of this approach would be the 1998 document Apostolos Suos, which held that episcopal conferences have no right to teach on matters of faith and morals in their own name. Most Americans, along with a large chunk of the rest of the Catholic world, regarded this a classic exercise in raw power politics. Faced with a wealthy, respected and influential national conference in the United States, and equally impressive regional conferences in Latin America and Asia, the Vatican wanted to cut them off at the knees. Many American Catholics were proud of the accomplishments of their bishops’ conference in the 1980s, with well-received documents on the economy and on peace. The idea that their bishops were being “punished” for such success was galling.

It should be understood, however, that seen through the eyes of the Vatican, Apostolos Suos was designed to bolster, not compromise, the authority of individual bishops, ensuring that their voice is not drowned out by an ecclesiastical bureaucracy. More broadly, some American bishops worry that too many decisions under John Paul have been reserved to Rome, violating the balance that should exist between unity and flexibility. The long struggle to bring the translation of liturgical texts into English under Roman control is one illustration. Bishops also frequently complain that John Paul’s advisers listen too much to disgruntled Catholics who happen to express a bias that is in favor in Rome, rather than a serious pastoral problem that requires an intervention. Finally, many American bishops are disheartened by the alienation and polarization that exists in the U.S. church among so many classes -- women, pastoral workers, theologians, activists. This is perhaps not the pope’s fault, but obviously he has not figured out a solution, and the bitterness has obviously become far more intense in the wake of the American clergy sex abuse crisis. “John Paul has been a great pope,” one American bishop said in the summer of 2003. “But he’s leaving behind a hell of a pile of unfinished business for the next guy.” Beyond Doctrine and Politics One could go on considering other groups -- African Catholics, for example, or young Catholics who have flocked to see John Paul as part of World Youth Day celebrations. But the point should be clear: This pope’s legacy is complex, and even from a single vantage point, one can usually find both light and shadows. So what can we say with certainty, not just from one or another point of view but in the absolute, about John Paul II, 264th successor of St. Peter, on the 25th anniversary of his election? First, he matters. He changed the face of Europe, stopped a handful of wars and inveighed against others, traveled the equivalent of three and a half times to the moon and has been seen in person by more human beings than anyone else in history. He has to be numbered among the titans of his time. This pope is indeed a magnet for humanity, including the 4.5 to 5 million people in Manila in 1995 for World Youth Day, and the 10 million in Mexico City in 1979. The only events that compare are the Hindu Kumbh Mela festival of January 2001, when 10 million people bathed in the Ganges River over 24 hours, and the funeral of the Iranian Muslim leader Ayatollah Khomeini in June 1989 that drew 3 to 10 million.

Second, one can say that precisely because John Paul matters, he also divides. He lives the title of the retreats he preached for Paul VI as archbishop of Kraków: a “sign of contradiction.” Everyone has an opinion on John Paul II, which is perhaps the most convincing sign of his impact. His 25 years in power have been a whirlwind of activity: 102 trips outside Italy, 474 saints, 1,314 beatifications, 14 encyclicals, and on and on … and the production continues. On the very day of his 25th anniversary, John Paul will release yet another apostolic constitution, this one the conclusion of the October 2001 Synod for Bishops. While all this activity has made the pope famous, it has also made him controversial. It has been a bruising, painful, polarizing pontificate, one of the reasons that some cardinals say his successor should perhaps be a quieter, less dominating figure, who doesn’t tower over the scene in quite the same way. Finally, one can say with confidence that Karol Wojtyla, deeper than his politics and beyond his early 20th century Polish Catholic cultural formation, is a mensch. He is a strong, intelligent, caring human being, someone whose integrity and dedication to duty represent a standard by which other leaders can be measured. For one thing, John Paul is a selfless figure in a me-first world. Cardinal Roberto Tucci, who planned John Paul’s voyages before retiring in 2001, once said he had briefed John Paul hundreds of times on the details for his various trips. Not once, Tucci said, did the pope ever ask where he was going to sleep, what he would eat or wear, or what his creature comforts would be. The same indifference to himself can be seen every time the pope steps, or today, is rolled, upon the public stage. This is the key that unlocks why John Paul draws enormous crowds, even where his specific political or doctrinal stands may be unpopular. It’s a rare ideologue for whom condoms or the Latin Mass represent ultimate concerns. Deeper than politics, either secular or ecclesiastical, lies the realm of personal integrity -- goodness and holiness, the qualities we prize most in colleagues, family and friends. A person may be liberal or conservative, avant garde or traditional, but let him or her be decent, and most of the time that’s enough. This realm of menschlichkeit, authentic humanity, is where John Paul’s appeal comes from. For a pope of a hundred trips and a million words, perhaps the most important lesson he’s offered is the coherence of his own life. When he urges Christians, in the words of Jesus, to Duc in Altum -- to set off into the deep -- it resonates even with those who seek very different shores. As Hamlet said of his father, perhaps John Paul’s admirers and critics together might be able to say of him: “He was a man. Take him for all in all, I shall not look upon his like again.” John L. Allen Jr. is NCR Rome correspondent. His e-mail address is jallen@natcath.org. National Catholic Reporter, October 10, 2003 |