|

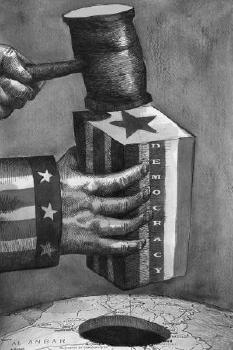

Issue Date: November 28, 2003 Behind the News -- Bush sets new course in the Mideast Analysts praise directive on democratization, but some wonder if action will follow By MARGOT PATTERSON On Nov. 6, President Bush delivered a foreign policy speech in which he pledged the United States to the advancement of democracy in the Middle East and repudiated “60 years of Western nations excusing and accommodating the lack of freedom in the Middle East.” The speech delivered at the 20th anniversary of the nonprofit National Endowment for Democracy represented at least rhetorically a major departure from U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East, a policy that historically had stability as its keystone rather than commitment to human rights or democracy. The strategy, said Bush, has not served the long-term interests of the United States because “stability cannot be purchased at the price of liberty.” Mideast scholars said the speech signaled a major formal change of U.S. policy in the region but added it remains to be seen whether the speech will be backed up by action. It should be viewed, they said, within the context of the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq. “We need to understand that the president’s speech is part and parcel of a major campaign on the part of the White House in order to respond to domestic criticisms about America’s strategy in Iraq,” said Fawaz Gerges, the Christian A. Johnson Chair in International Affairs and Middle East Studies at Sarah Lawrence College and the author of America and Political Islam: Clash of Cultures or Clash of Interests? “The speech was informed by America’s challenges in Iraq itself.”

“The problem I have with the speech is whether it is really intended to reflect a change of policy in the region or is intended to make Americans feel good about what we are doing in Iraq -- that is, to give a positive vision for what lies ahead for Iraq and the rest of the region,” said Quandt. “The missing ingredient in the speech -- and we don’t know yet about the policy to come out of it -- is will there really be any carrots and sticks attached to it? Will our relationship with Egypt change? Will our relationship with Saudi Arabia change or is this just a way of having a rhetorical club to beat Syria and Iran with?” Quandt said Egypt, a long-standing U.S. ally valued both for its stability and its willingness to make peace with Israel, will be a test case of whether the United States is serious about democratization. “If we don’t try to encourage Egypt in the direction of greater democracy, then a lot of people are going to look at it and say nothing has changed. This is just ‘feel good’ stuff,” Quandt said. That is, in fact, the perception of most Middle Easterners, said Ian Lustick, a professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania and a consultant on the Middle East to four presidential administrations. “President Bush never mentioned Israel in his talk. From the point of view of most of his listeners, this is proof positive that it’s not a serious speech. It’s a vision cooked up to justify what some in the administration want to do in Iraq. That is the reality of what Middle Easterners think.” Lustick said it was striking that Bush’s speech cast democratization as the main concern of U.S. foreign policy. “It’s hard not to notice that WMD [weapons of mass destruction] was not even mentioned in the speech. This is a virtual transformation in the justification for the war, taking it from a minor theme to the major objective. The fact is, as it’s heard in the Middle East, this is not really a change because this is more of the United States saying one thing and doing another.” Historically, said Lustick, the United States has looked the other way when it comes to democratization and human rights in the Middle East because of economic and strategic interests. Lustick said the administration’s dealings with Jordan since 9/11 and the start of the war on terrorism suggest that this has not changed. “I urge you to take a look at Jordan because of the effect the U.S. build-up against Iraq has had on reducing democracy in Jordan,” Lustick said. “They’ve been rewarded because of it with an increase in aid. Very draconian laws have been passed that make it illegal to criticize the government. That’s not the kind of policy Americans usually think of as democratization, but those are the policies that are being rewarded in the war on terrorism.” In Iraq, too, scholars said the U.S. commitment to democratization is open to question. “We can look at Iraq where the governing council was not picked to reflect the wishes of most Iraqis living in the country right now. It’s dominated by exiles, and it would have been more so if the original plan had gone through,” said Mary Ann Tetreault, a professor of international affairs at Trinity University in Texas and the author of Stories of Democracy: Politics and Society in Contemporary Kuwait. While there may be a greater move to democratize as a way of reducing U.S. military commitments, Tetrault said, “The commitment to democratization in Iraq is murky at best. “Democratization is very hard,” she said. “You’ve got to have a great deal of confidence in people on the ground. You have to be willing to be very transparent in your dealings with people, and you can look at Iraq and there’s been a great lack of transparency. The way decisions are made is not transparent. We have a proconsul who is making decisions, and the people on the governing council are agitating for greater authority, and if you look at their own status they didn’t come from anywhere. There was a poll done a few weeks ago in Iraq, and huge numbers of people don’t know who these people are. There is still not much progress at all in opening up the system to have Iraqis participate in deciding what kind of governance they’re going to have in their own country.” Democracy evolves within a culture, said Tetreault. It does not trickle down but moves up. “If we’re applying top-down governing methods to democratize, we’re not going to get much democratization that springs up from the bottom,” she observed. While noting President Bush’s speech said many useful things, Tetreault said she had some concerns about how well thought out the administration’s plan was to democratize the Middle East. “ ‘Democratic values’ is not just about holding elections. It’s about political participation, about being able to express your views in public, of having a system that tries not to discriminate against minority groups.” She remarked that some officials in the administration who are talking about democratization are probably talking as much about economic liberalism and openness to U.S. investments as political democracy. And as much as President Bush’s speech may have been about redirecting U.S. policy to uphold democracy, Tetreault said it was also a warning to various nations in the Middle East. “There has been a great deal of pressure, not only on Iran and Syria, which has had to put up with an awful lot of threats in the last few months, but also the countries of the Arabian Gulf. There’s been a not very well concealed assault against Saudi Arabia by a number of people in the administration,” Tetrault said. “This is another gauntlet being thrown down. It reflects even dissent within the administration whether the moves the Saudis have been making for elections to municipal councils are enough.” Despite uncertainty about whether the president’s rhetoric will be matched by concrete political initiatives supporting it, Gerges said the speech was important in and of itself. “First and foremost, this is the first time in U.S. history that a president explicitly states that for the last 60 years American foreign policy has tried to maintain the status quo and did not invest in democratic values, in human rights, in the rule of law,” Gerges said. “Regardless of what one thinks of the context, it’s a major acknowledgement that American foreign policy did not live up to the ideas of what America is all about. Secondly, the importance of the speech is that it represents a major retreat on the part of the Bush administration in the rhetoric of the neoconservatives about using shock tactics to shake the Arab world out of its political slumbers. Now the emphasis is on a peaceful, gradual approach that takes into account local sensibilities and local cultures. The president made it very clear that democratization does not mean Westernization or Americanization. The speech was enlightened, nuanced, and allies the United States with civil societies as opposed to oppressive dictators of the Middle East.” Gerges said the president’s commitment to democracy will be measured in three areas. Will the president exert pressure on America’s local allies in the Middle East to structurally reform their closed political systems? Will the president invest adequate political capital in order to achieve an equitable and just settlement to the Arab-Israeli conflict? Will the Bush administration take risks on behalf of people’s choices in Iraq by replacing military occupation with an elected legitimate Iraqi authority? “The democratization of the Middle East is not a matter of a year or two or three. It’s a highly complex process. It will take decades, more than a generation, to really lay the basis for a democratic society,” Gerges said. Margot Patterson, an NCR staff writer, frequently reports on the Middle East. Her e-mail address is mpatterson@natcath.org. National Catholic Reporter, November 28, 2003 |

William B. Quandt, professor of government and foreign affairs at the

University of Virginia, called the decision to go into Iraq a watershed moment

for U.S. policy in the Mideast. Quandt was a member of the National Security

Council in the Nixon and Carter administrations who helped negotiate the Camp

David peace agreement reached under Carter. Bush’s speech, he said, is

“part of the refocusing of U.S. policy in the Middle East [to] make this

turn out for the best.”

William B. Quandt, professor of government and foreign affairs at the

University of Virginia, called the decision to go into Iraq a watershed moment

for U.S. policy in the Mideast. Quandt was a member of the National Security

Council in the Nixon and Carter administrations who helped negotiate the Camp

David peace agreement reached under Carter. Bush’s speech, he said, is

“part of the refocusing of U.S. policy in the Middle East [to] make this

turn out for the best.”