Issue Date: January 9, 2004

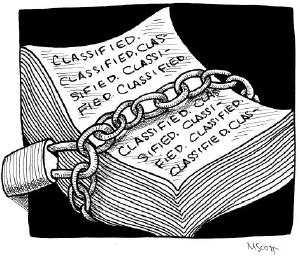

Critics say Bush refusal to release records is more about politics than security By JOE FEUERHERD In what may be one of Washington’s best-kept secrets, the volume of federal government information deemed confidential is three times larger today than just five years ago -- from 8 million such classifications in 1999 to more than 23 million in 2002. It’s a good bet that 2003’s numbers, once tallied by the government’s Information Security Oversight Office, will be even higher. And it’s not just the records of Vice President Dick Cheney’s energy policy task force (the continued confidentiality of which will be decided by the Supreme Court) or sensitive military or antiterrorism information such as intelligence sources or battle plans that are beyond public scrutiny. In March President Bush cited fears of bio- and agro-terrorism when he extended “classification authority” to the Department of Health and Human Services, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Agriculture. Meanwhile, the volume of governmental information not officially classified but still withheld from Congress, the media and the public continues to grow. The tone was set early. Soon after taking office, Bush used an executive order to overturn practices related to the disclosure of material from prior administrations, including those of his father. Under previous interpretations of the Presidential Records Act, most information would be disclosed beginning 12 years after an administration left office. Under the Bush order, previous presidents (and the incumbent) have the right to restrict disclosure indefinitely. From its first days the Bush administration made clear its intention to vigorously assert “executive privilege,” the concept that the deliberations of the executive branch are subject to congressional and public oversight only to the extent that the administration wants them to be. Conservative congressman Dan Burton, R-Ind., chastised the Justice Department for failing to release information related to presidential pardons granted by President Clinton, disclosure of which Clinton himself supported. In another congressional investigation -- this one involving alleged FBI malfeasance in the case of a Massachusetts man falsely accused of murder -- Burton told Justice Department officials that “your man is acting like a king” in refusing to release records. “It is the most secretive administration going back to Nixon or even before Nixon,” former Clinton White House Chief of Staff John Podesta told NCR. “It is striking, quite frankly, how much they have done to push back an almost 50-year trend of more open government.” A five-month investigation into Bush administration secrecy practices by U.S. News and World Report highlighted a pattern of confidentiality that expands beyond national security issues. The administration, the magazine reported in its Dec. 22 issue, is withholding information on a range of consumer issues (including auto and tire safety reports prompted by the Firestone tire fiasco), limiting disclosure of local environmental hazards, and aggressively asserting dubious national security claims in both civil and criminal cases. Of the latter, said U.S. News, “It is impossible to say how often government lawyers have invoked the privilege.” Environmentalists, meanwhile, contend the Cheney task force’s May 2001 report was overly influenced -- and in some cases drafted by -- business leaders whose industries would benefit from less regulation or government investment. “At some point, the Bush administration is going to have to realize that the American people want to know what kind of influence energy corporations had over America’s energy policies,” said David Bookbinder, senior attorney for the Sierra Club. “The public deserves to know who actually wrote these plans.” What the public, the press and Congress deserve to know is at the heart of disputes over what should be released and what should be withheld. As a matter of policy, the administration favors limited disclosure. “I have a duty to protect the executive branch from legislative encroachment,” Bush told a March 2002 news conference. “I receive advice and in order for people to give me sound advice, that information ought not to be public,” said Bush. “Somebody is not going to walk into the Oval Office thinking that the conversation is going to be public and give me good, sound advice.” Just last month, in signing legislation to reauthorize foreign intelligence activities, Bush gave himself a big exemption from congressional oversight of the nation’s spymasters: “The executive branch shall construe the [disclosure] provisions in a manner consistent with the president’s constitutional authority to withhold information the disclosure of which could impair foreign relations, national security, the deliberative processes of the executive, or the performance of the executive’s constitutional duties.” Congress largely cowed Along with Republican Burton, some congressional Democrats have challenged Bush secrecy policies. In November 2001, Reps. Henry Waxman, D-Calif., and Janice Schakowsky, D-Ill., argued against Bush’s interpretation of the Presidential Records Act. “The goal of the law,” the two lawmakers said, “is the orderly and systematic release of records -- not the indefinite suppression of these historically important documents.” House Judiciary Committee ranking member John Conyers, D-Mich., has been among the administration’s most vocal critics. “Since the horrific events of Sept. 11, this administration and the attorney general have taken a series of constitutionally dubious actions that place the executive branch in the untenable role of legislator, prosecutor, judge and jury,” Conyers said last year. “What is even more troubling is that the Justice Department is acting in this manner in complete secret; it refuses to disclose to those it is protecting -- the American public -- how it is conducting the war on terrorism.” But Burton, Waxman, Schakowsky and Conyers are the exception, not the rule. Congress is largely mute. “We have in both houses of Congress a majority party that is the same as the party in the White House,” explained Steven Aftergood, director of the Federation of American Scientists’ Project on Government Secrecy. “As a result, much of the natural adversarial tension has been muted and Congress is much less likely to request, to insist, to subpoena and to make secrecy an issue.” Critics cite a number of indicators that they say show a growing culture of secrecy:

National security concerns and presidential prerogatives, whatever their validity, don’t account for the entire uptick in government secrecy, says Aftergood. More than 4,000 federal employees have “original classification authority” -- the ability to create new secrets. Decisions to keep some things secret are “often made by individual program managers who often have an exaggerated notion of the sensitivity of their particular program,” said Aftergood. He offered this example: “Say you want information about a local environmental matter -- what type of toxic materials are stored next to your children’s schools -- [and they say] we can’t disclose that because of the threat of terrorism. It is a common argument. In the abstract one can’t dismiss it altogether. But on close inspection what one finds over and over again is that agencies are withholding information indiscriminately while invoking the specter of terrorism.” Aftergood is suing the CIA, seeking information on the amount of government spending on intelligence. He doesn’t want the details, just the overall budget figure. His request for information on the agency’s 1947 budget was denied. The CIA argues that release of even half-century-old information will lead to a “slippery slope,” said Aftergood, “and the next thing you know the names of our agents in Baghdad will be in the newspaper.” That, said Aftergood, is “either delusional or dishonest.” Joe Feuerherd is NCR Washington correspondent. His e-mail address is jfeuerherd@natcath.org.

National Catholic Reporter, January 9, 2004 |