Issue Date: January 16, 2004

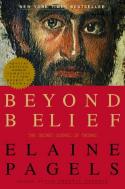

By CHRIS HERLINGER On a recent book tour, Elaine Pagels was asked more than once if she was trying to discredit or even destroy the Bible. The answer was a polite, firm and occasionally exasperated “no.” Such questions are hardly novel for the renowned historian of early Christianity, and Pagels has come to expect everything from puzzled queries to heated polemic to greet her work. “Oh, this was gentle,” she said of the stinging rebuke of one critic, a fellow scholar who, to put it charitably, did not like her latest book, Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas. The critic, Luke Timothy Johnson, said Pagels adhered to a “stunningly simple argument.” Beyond Belief, published by Random House, found itself on The New York Times bestseller list earlier this year and was also a Times “Notable Book” for 2003. It was, the Times noted, something of a “surprise hit” given it was penned by a Princeton University professor and concerned itself with an early Christian text still little known to the general public. In the book, Pagels examines the Gospel of Thomas, one of the noncanonical texts -- a set of writings sometimes called the “Lost Gospels” -- rediscovered in 1945, and explores why the text was not included in what eventually became the New Testament.

If Thomas believed humans should try to emulate Jesus as a way of discovering inner divinity, John’s Gospel “succeeded ever after in persuading the majority of Christians,” Pagels writes, that “only by believing in Jesus can we find divine truth.” In some ways the commercial and critical success of Beyond Belief is hardly a surprise: Pagels, who initially garnered wide attention with her 1979 book The Gnostic Gospels, is one of the few religious scholars who write for a general audience. Pagels is also among a handful of scholars -- Harvard University’s Karen King, the author of a new book on Mary Magdalene, is another -- who find themselves in the curious position today of having their work interpreted in the popular media in relation to the bestselling novel The Da Vinci Code. That novel raises questions about the origins of the early church, including the possibility that Jesus may have been married, perhaps to Mary Magdalene. Pagels, interviewed recently in her comfortable Princeton home only a day after breaking an ankle in a running accident, chuckled at the memory of her appearance on a nationally televised program. The broadcast all but treated the author of The Da Vinci Code as a scholarly authority on the early church. “Are you pretending this is history?” she remembers thinking, but added that the success of the bestselling novel is no fluke: This is a time when many Americans -- some searching for spiritual meaning, others weary of church hierarchies -- are asking what she calls legitimate questions about religious authority. One result of this is that Pagels, 60, is quietly buoyant that something of the unifying theme, the connecting thread, of her scholarly work is now receiving wider public attention: Texts like Thomas and those of the Gnostics, she argues, reveal a more diverse early Christian landscape than was ever imagined. “The history of Christianity is not a triumphal march of ideas but a series of intense arguments and conversations,” Pagels said. “I love that side of it.” Others are less enthusiastic. In a review for the independent Catholic magazine Commonweal, Johnson, who teaches New Testament and Christian origins at the Candler School of Theology, took Pagels to task for needlessly defending noncanonical texts that honor spiritual experience over “the rule of faith (or creed).” “Welcome to another exercise in revisionist history,” Johnson wrote, adding that Pagels’ “historical point is that the good stuff lost out. Her normative point is that Christianity has to claim its inner Kabbalah [Jewish mysticism] if it is to appeal to people like Elaine Pagels.” Pagels understands Johnson’s critique, but maintains she is not so much saying that “the good stuff lost out” as arguing that contemporary Christianity is richer by having a wider range of early texts from which to draw. As for embracing Kabbalah, Pagels said the church should do exactly that. But, she added, she is not arguing that works like Thomas should or can be appropriated as “New Age” signposts. “Texts that are 2,000 years old are not that new,” she notes. The Gospel of Thomas and other works, she said, “speak about an experiential path toward the spirit rather than a set of doctrines” but remained rooted in the Christian tradition. Pagels’ need to embrace a wider spectrum of early Christian literature stems in part from tragedy that she touches on only briefly in the book: In late 1987, Pagels lost a young son to a rare lung disease. Compounding that loss, her husband perished in a climbing accident a little more than a year later. “I’m not the first person who has grieved and who has found a set of established beliefs so remote,” she said. In the book, she recalled how this experience prompted something of a quest, asking how and why “being a Christian became virtually synonymous with accepting a certain set of beliefs.” Calling herself a nondogmatic liberal who tries to be fair and “treat people all over the theological spectrum with respect,” Pagels credits liberals with being more conscious of the ways authority shapes and develops church tradition. To the conservative charge that contemporary liberal Christians are apt to “pick and choose” what they believe, Pagels said that “picking and choosing” is, in fact, a characteristic of two millennia of Christian history. “For 2,000 years we’ve been picking and choosing, asking and raising questions based on new issues that emerge in societies,” she said. “The real question, if someone says, ‘I follow the Bible,’ is to ask, ‘Which parts of the Bible, at the beginning of the 21st century, do you follow?’ ” National Catholic Reporter, January 16, 2004 |

Pagels argues that early authority figures within the church,

particularly Irenaeus, the bishop of Lyons, concluded that the writer of the

Gospel of Thomas erred in suggesting that Jesus taught “that we have

direct access to God through the divine image within us,” Pagels writes.

In contrast, the majestic Gospel according to John -- which Pagels believes was

probably written in response to Thomas, with the two texts “in

dialogue” but also often in conflict -- took a far different view of Jesus

and his ministry and proved more useful in uniting the growing Christian

movement.

Pagels argues that early authority figures within the church,

particularly Irenaeus, the bishop of Lyons, concluded that the writer of the

Gospel of Thomas erred in suggesting that Jesus taught “that we have

direct access to God through the divine image within us,” Pagels writes.

In contrast, the majestic Gospel according to John -- which Pagels believes was

probably written in response to Thomas, with the two texts “in

dialogue” but also often in conflict -- took a far different view of Jesus

and his ministry and proved more useful in uniting the growing Christian

movement.