Issue Date: February 6, 2004

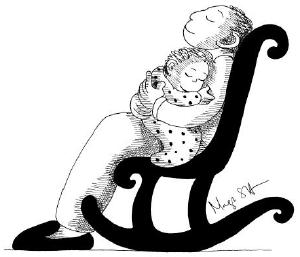

By MICHAEL McGIRR Our little boy is 40 days old. We have called him Benedict. St. Benedict was a hermit who lived in the fifth century at a time when the Roman Empire was collapsing. He lived in uncertain times. Everybody does. At the insistence of friends, St. Benedict agreed to lead a community of monks. He wrote a rule for them called, of course, the Rule of St. Benedict. It is a humane and sensible approach to living a radically Christian life. The original Rule of St. Benedict says that strict silence should be observed at night. Our Benedict seems to want to live by a rule of his own in that regard. St. Benedict understood that nighttime was a natural time for prayer. The main reason for this, I think, is that he saw prayer as a form of listening. The first word in the Rule is “listen.” It begins by asking people to “listen with the ear of the heart.” Throughout the rule, the word “listen” comes up again and again. It seems to be the only hard and fast instruction Benedict wanted to give. Perhaps that is why he said that spoken prayers should be brief. He didn’t want people to be such chatterboxes that God couldn’t get a word in edgeways: “We must know that God regards our purity of heart and tears of compunction, not our many words.” The one psalm Benedict asked monks to say every single day was Psalm 94. It includes the words, “If today you hear God’s voice, harden not your hearts.” For Benedict, the ear and the heart seemed to be joined together. You learn that when you have a baby. Every time he laughs or cries or gurgles, it touches something in us. Before our Benedict was born, one of our friends e-mailed us to say that the two things every parent needed were a pair of earplugs and a subscription to pay-TV. Needless to say, he was joking. Or maybe only half joking. He said there was nothing decent on TV in the middle of the night (unless we liked the infomercials) and we would need something to occupy us when we were keeping vigil with our baby. Every parent knows that being up in the middle of the night can be a bit of a drag. But we have also noticed how still the rest of the world is at that time. You notice subtle sounds that, during the day, are just background noise. We can count the cars on the railroad trains as they lumber past; we notice the small sounds of nature as it stirs from rest at some ungodly hour. Holding a child in the middle of the night is a good way to pray. You’re not always sure what to do or even how you are going to cope. You dream of a wonderful future for the child but wonder how you will make it through the next day. All you can do is trust. St. Benedict is often said to be the founder of Western Christian monasticism. I prefer to think of him as the man who called the extreme Christians in from their deserts and caves and challenged them to be homemakers. His rule is full of homely advice about how much to eat and drink, how much to sleep, how to look after the young, the old and the weak, how to forgive those you live with. He is well known for urging moderation in all things. His rule suggests that radical Christians should be happy. In its time, this was uncommon sense. For him, home and the monastery were one and the same place. He said, “As we progress in the monastic life and in faith, our hearts will swell with the unspeakable sweetness of love.” The same applies, I am sure, to any growth in unselfish love. Benedict hoped that his followers might grow in three areas in particular. He named them as humility, stability and hospitality. The first two come together. We all recognize who are the stable people in our lives. They are often the ones with quiet self-confidence. They seem happy to be themselves with all their good and bad points. They are not egotistical, nor are they too hard on themselves. That is not real humility. Real humility is something like self-acceptance. And it’s funny how often the stable people are the ones we turn to in times of need. We are glad they are just there. We are grateful for the hospitality of their hearts. All of this is a lot to lay on our little Benedict. We often pray that he will be able to appreciate some of the things that his namesake was talking about; we pray that he will know peace. But we have just as much to learn ourselves. An e-mail from another friend assured us that Benedict would be a good teacher. She said we would learn how to be his parents by listening to him. Michael McGirr is the former editor of Australian Catholics and publisher of Eureka Street, both of which emanate from Jesuit Publications in Melbourne. His book Things You Get For Free was published in the United States by Grave Atlantic in 2003. National Catholic Reporter, February 6, 2004 |