Issue Date: February 6, 2004

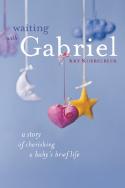

Author’s tale of her child’s brief life finds a glimmer of beauty amidst dark sorrow Reviewed by KRIS BERGGREN Waiting With Gabriel is a quick read -- in fact, it’s a page-turner-- but it’s not an easy read. The book by reporter Amy Kuebelbeck details her experience of learning, five and a half months into her third pregnancy, that her unborn baby, whom they eventually named Gabriel, had a fatal heart condition. Kuebelbeck deals objectively with the facts surrounding the choices available to her and her husband, and honestly with her family’s feelings about the choices they made and the ones they didn’t. If you have ever had an ultrasound with an uncomplicated pregnancy, you will know how thrilling it is to lie in that dark room looking at the black and white images of your forming child, how reassuring the technician’s commentary on the baby’s in utero activity or particular body parts. Many a proud parent passes around the first ultrasound image even before the delivery room snapshots. If you have ever had an ultrasound revealing unwelcome news, you will recognize the unreal feeling Kuebelbeck describes as she and her husband learned that her otherwise perfect baby had HLHS, or hypoplastic left heart syndrome. “To me,” she writes, “it felt like falling backward, as though the tiled concrete floor, the clay underground, all the subterranean layers of rock were simply and soundlessly parting to let me through to some other dimension.”

Indeed, I suspect that the death of an infant or a child initiates one into a surreal club that must feel separate from the real world. I’ve been close to two families who have experienced the deep, immense pain of the stillbirth of their full-term babies, and I would say there is nothing like that particular kind of grief over a life already dreamed but never lived. Kuebelbeck writes with grace about the continual waves of grief that occur when your milk comes in and there is no baby who needs it; when you wonder what to say when somebody asks how many children you have; when merely attending somebody else’s baby shower can be difficult. According to Kuebelbeck’s research, HLHS occurs in one of about every 5,000 births, affecting about 1,000 U.S. babies annually, two-thirds of them boys. The cause is indeterminate and there is no cure. It is marked by severe malformations on the left side of the heart, which prevent the organ from doing its job of pumping blood to the whole body. Babies born with the condition may live for a few hours or a few weeks. Perhaps wearing her reporter’s hat enabled Kuebelbeck to do the difficult research involved in deciding what to do about Gabriel. Parents of babies with HLHS have several options. Although late-term partial-birth abortion is legal in some states and practiced in cases such as this, when the baby will not live, Kuebelbeck and her husband decided this was not for them. Their postnatal options were three: One is a series of painful palliative surgeries that may prolong the baby’s life indefinitely, in the hope that a cure might be discovered, but which result in a lifetime of medical interventions, difficulty breathing -- far from a normal childhood. As one nurse told Kuebelbeck, “There are some things worse than death.” A second is the slim chance of a heart transplant, should a donor heart become available. The third, and the one that Kuebelbeck and her husband chose, is to provide “comfort care” -- to simply allow the baby to live a peaceful, if brief, life and to die a peaceful, pain-free death. In a way, Kuebelbeck and her family, including their daughters Maria and Elena, then ages 4 and 2, were lucky. Their grief was shared by their extended families and friends. Their strong faith sustained them and provided context and ritual for Gabriel’s short life and death. Also, knowing Gabriel’s condition ahead of time gave them time to plan for the baby’s baptism and funeral. And they are lucky to live in an age when grief over an infant’s death “counts.” In previous decades, mothers whose babies died at birth were often not even allowed to see the baby, much less to hold a funeral or to grieve openly -- and fathers’ feelings were not even acknowledged. Even today, people still offer platitudes like, “You’re young, you can have another baby,” or “God must have needed another angel in heaven,” but, increasingly, parents whose child dies are permitted, even encouraged, to grieve fully. Indeed, some cemeteries are providing monuments or areas for babies and children and where even parents whose babies have died decades ago may engrave their child’s name as a permanent marker, as Kuebelbeck’s family decided to do. They used money donated in memory of their son to provide “Gabriel’s Boxes” to the hospital to be given to other parents whose baby dies in late pregnancy or shortly after birth; the boxes include materials for commemorating their child’s life and dealing with grief. For example, one item in the kit is a baby book specifically for babies who die -- no pages dedicated to “baby’s first tooth” or “first word.” Waiting With Gabriel also touches lightly on the mystical moments Kuebelbeck experienced during and after the pregnancy that point to a transcendence -- the author’s unusual tears during a moving rendition of “Silent Night” during a Christmas concert may, she reflects in retrospect, have been a premonition of her baby’s death. Months after Gabriel’s death, a chance encounter with a nurse who cares for babies with HLHS reaffirms Kuebelbeck’s choice to provide comfort care -- and it is made more poignant by the fact that the nurse had dreamed about a boy named Gabriel the previous night. Although grieving a child is a lonely place, such moments of light are a beacon of hope. This book is one such glimmer of beauty amidst the dark sorrow, a resurrection message appropriate for an Easter people. Kris Berggren is the author of Strategies for Stay-at-Home Parents (Meadowbrook Press, 2003) and an NCR columnist. Her e-mail address is krisberggren@msn.com. National Catholic Reporter, February 6, 2004 |