|

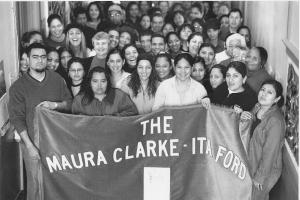

| Staff and students at the

Maura Clarke-Ita Ford Center. -- Photos by Amy Elliot |

Program named for Maryknolls marks 10 years educating immigrant women

By RETTA BLANEY

Brooklyn, N.Y.

The one overwhelming impression from a visit to the Maura Clarke-Ita Ford Center is that it is a peaceful place. A reverent quietness permeates, despite the challenging and often painful lives of the poor, mainly immigrant women of Brooklyn’s Bushwick neighborhood who come here. The words of Maya Angelou displayed on one wall capture the feeling: “Nothing can dim the light which shines from within you.” That sense of empowerment seems to fuel the quiet attentiveness of the women studying as they seek skills to understand and be understood in their new country.

“It’s so easy to work here,” said Sr. Mary Burns, a sister of Charity of Halifax who is founder and director of the center, which is named for two American Maryknoll sisters who were murdered in El Salvador in 1980. “Everyone’s here to learn.”

|

| Sr. Mary Burns |

Whether their arrival in this country has been as dramatic as slipping undetected across a border or as routine as boarding a plane, the women at the center have come just as thousands of immigrants before them, looking for financial and sometimes political security, especially for their children.

“They all have their own stories of how they got here, but they all want education for their children,” Burns said. “That’s the key, I think.” Learning English was the primary interest of about a half-dozen women who, either in broken English or through an interpreter, talked one recent morning of wanting to help with homework, deal with school matters or just be a better educated parent.

“You can live in Bushwick and never speak English,” Burns said.

Rosa is a good example of this. (Last names are withheld because many of the women are undocumented.) Although she arrived in this country 13 years ago from El Salvador, she speaks little English. She enrolled at the center four months ago because she hears her children, aged 7, 12 and 15, speaking English to their friends on the phone and wants to know what they are saying. When she asks them, they won’t tell her. Before coming to the center she spent her time at home eating and sleeping too much. Now she says she has made friends and feels accepted.

The majority of the women who come here are between 20 and 40, but their educational backgrounds range from “no chance to go to school in their own country to college graduate,” Burns said. All are asked to pay $10 a month, for which they may take as many classes as they like.

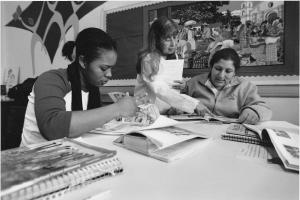

|

| Teacher Awilda Heredia, center, helps students Altagracia, left, and Rosa. |

“If you pay for your education, you have a right to complain,” she said. “It’s an ownership, too.”

Burns conceived the idea for a women’s center while between jobs and on retreat on Long Island in 1989. It took several years for the vision to become a reality, but on Sept. 7, 1993, the center opened in a former elementary school, space rented to it by St. Barbara Parish. The need is great in Bushwick, an area formerly known as “burnt-out Bushwick” because of the devastation it suffered in the rioting following the 1977 blackout.

Mexicans are the dominant immigrant group, followed by those from the Dominican Republic and Ecuador. Tiny shops line the commercial streets, offering nail and hair care, carryout ethnic foods and the wares of small grocery stores. A sprawling housing project, Hope Gardens, has replaced homes destroyed in the riots. The school district was rated one of the worst in the city last year; only 20 percent of eighth graders passed their standardized reading tests.

In its first decade, the center has helped at least 1,200 neighborhood women develop language and computer skills, acquire GEDs and participate in leadership training. On an average day, about 90 attend classes while many of their children are helped in Head Start programs on the floors below. And while the Head Start efforts are not part of the center’s work -- the building is home to many social service agencies -- children’s needs are also part of the center’s outreach. Burns and the teachers talk to the women about their children and if they learn of any difficulties at a school, they help organize a group of women and prepare them to talk to the principal or other school officials.

“The teachers know what’s going on,” Burns said. “They’ll let us know if something’s happened.”

This kind of advocacy helped one child with attention deficit disorder get transferred to a smaller school where he is thriving.

“The sacrifices these women are making to be here are for their family,” Burns said. “We want to make sure it’s worth it.” Such support is the center’s aim. “Never do for others what they can do for themselves. That’s what we try to work on here.”

|

| Wendy, a student at the center, takes part in a class. |

The center’s first decade of service is being honored in March by a choral drama written by Elizabeth Swados, a composer whose work has appeared on and off Broadway and around the country (see accompanying story). It will be a fundraiser for the center that Burns, “in my dreams,” hopes will raise $50,000 to increase teacher salaries, offer more classes and just “not to have to worry about money all the time.” The center’s annual budget is about $380,000, but “sometimes it’s not enough. It’s always a concern.”

As she has been from the start, Burns is compelled by her horror at the murders of Clarke, Ford and two other American missionaries in El Salvador in 1980 and her desire to honor their memories. Although she never knew any of the women, she named the center for Clarke and Ford because they were from Queens and Brooklyn.

“When I get to heaven, one of the first things I’m going to ask them is ‘Why me?’ I’m a Sister of Charity and they were Maryknolls. I got stuck. It’s a good stuck, but I’m stuck. It’s like a holy obligation for me.”

Retta Blaney’s latest book is Working on the Inside: The Spiritual Life Through the Eyes of Actors.

| Fundraiser born from composer's loyalty When composer Elizabeth Swados premieres her newest work, “Ten Years of Hope,” in March, she will be presenting more than a staged oratorio about the lives of immigrant women from Central and South America. She also will be demonstrating her loyalty to Roman Catholic nuns, something that would have been unthinkable to the Jewish composer before she wrote “Missionaries,” her choral drama about the ministry and murder of three American nuns and a church laywoman in El Salvador (NCR, Nov. 17, 2000). When the story of the murdered women made front-page news in 1980, it lodged forever in Swados’ soul. She began to respect women who work for “no gain or profit except in their hearts.” And when “Missionaries” received less than enthusiastic response in its premiere at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, women religious voiced their support and helped to revive the show. So when two nuns from a Brooklyn women’s center named for two of the murdered women, Maryknoll Srs. Maura Clarke and Ita Ford, asked Swados to write something as a fundraiser for the 10th anniversary of the center, she said yes. “Jews don’t forget,” she says. “These nuns were there for me artistically when my show was being badly treated and I was very upset. Because of them the show had a life. I’ll never forget that. It’s loyalty with a nose punch, a Mafioso of Jews and Catholics. They provided a life for what I consider my baby.” “Ten Years of Hope” (the name was chosen by the sisters) tells the stories of the women who come to the Maura Clarke-Ita Ford Center -- the hardships they endured at home, the struggles they face here and the transformation they experience at the center. The show also will feature the ministry of Sister of Charity of Halifax Mary Burns, the center’s founder and director, and Ursuline Sr. Mary Dowd, former codirector who recently retired. Clarke and Ford will be evoked either by using material from “Missionaries” or drawing from their letters or journals. “We’re keeping the memory of what [Clarke and Ford] stood for,” said Burns. “They didn’t die in vain.” Swados has been working on “Ten Years of Hope” off and on over the last six months as her schedule permits. She will receive no money, but the six professional singers and two musicians will be paid. Whether the work will have a life after its one-night performance March 6 at St. Luke’s Lutheran Church in the theater district is uncertain. “In this economy and with this government, I don’t have any idea of anything moving on,” she said. “I just do my work. I’m lucky I do as much as I do.” She said she continues to think daily of the murdered women she paid tribute to in “Missionaries.” “They represent something so important to me that I don’t always follow but wish I could. It’s the notion of giving without needing to get anything back, the pure gift. They were gutsy enough to stay in an area like that and give their lives. It’s hard to forget that.” -- Retta Blaney |

National Catholic Reporter, March 5, 2004