Issue Date: March 26, 2004

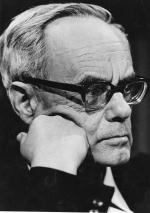

Remembering Karl Rahner on his centenary By LEO J. O’DONOVAN In these days between the 100th anniversary of Karl Rahner’s birth on March 5, 1904, and the 20th anniversary of his death at age 80 March 30, 1984, I have been thinking back especially on several visits I had with him in his last years in the Jesuit residence at Innsbruck, Austria. He is buried nearby, in the Church of the Holy Trinity. From the beginning Karl felt comfortable during this “third time” in Innsbruck (1981-84). After retiring from the University of Münster in 1971, he had moved back to Munich and lived at several Jesuit residences. Then, on Nov. 19, 1981, he returned to the city where he had first taught before and after World War II. Now, he wrote to a friend in the United States, he was “looking for a place to die.” These last years, however, were amazingly productive, not least because of the editorial assistance of Paul Imhof and the great support, as Karl himself said, of “the best secretary I’ve ever had,” Elfriede Oeggl. Two further volumes of his Schriften zur Theologie were published, along with smaller volumes on Christology and ecumenism. And it was Karl himself who often wrote his own letters late into the evening. He also continued to travel widely. In 1982 he gave lectures in 18 different cities, among them a trip to Tübingen May 14 to receive the Leopold Lucas Prize from the Evangelical Theological Faculty there. That year also saw two significant anniversaries for him, his 60th year as a Jesuit on April 27 and his 50th as a priest on July 31. On the first of these occasions his homily posed some of his typical, searching questions: “But when after so many years we look back on our life, then we don’t really know in the end what all we have failed to do, what tasks we passed by in guilty blindness and left undone, tasks that we might have addressed only if we had an entirely different attitude with which to master the deeds and suffering of our days. How much time that could have borne eternity did we leave empty, what might all have come to be that didn’t come to be? Haven’t we often been silent in a cowardly way, when we should have spoken, or spoken loudly? … When we think of our martyrs, didn’t we come too easily indeed through the Nazi time? Haven’t we sometimes in fact understood the aggiornamento of the [Vatican] Council too much in the sense of our own mood and comfort? “In this sense one could still ask many questions,” he continued, “and so an uncanny feeling comes upon us.” In 1983 he traveled to 20 cities for lectures, including a trip to Paris to be presented with the French translation of his Foundations of Christian Faith. That October I called him from Rome to tell him that Fr. Peter-Hans Kolvenbach had been elected the new Jesuit superior general at their 33rd General Congregation. (“Is he a nice fellow?” he asked on the phone.) I then journeyed to an already wintry Innsbruck to tell him about the congregation. We walked through the snowy town beneath the great mountains and talked about the mission of the Society of Jesus, letters from Rome, everyday faith. He was encouraged to hear about the courage and fidelity of Jesuits around the world. By the first few months of 1984 he had already given a retreat for priests in Italy and spoken on various occasions in Germany, England and Hungary. It seemed particularly fitting that on his 80th birthday he was able to receive the first printing of Prayers for a Lifetime. But the day I treasure most in Karl Rahner’s company was Ash Wednesday of that year, a story I’ve told in part before in Bilder eines Lebens (1985). On Monday of that week, friends from far and near had gathered to celebrate his birthday. A man with distaste for any cult of personality whatsoever, he had nevertheless appreciated the outpouring of admiration and affection, just as he had 20 years earlier when the massive two-volume festschrift Gott in Welt was published in honor of his 60th birthday. After lunch on Wednesday we took his car first to Schloss Tratzberg, where he had been under quiet house arrest with the Enzenberg family after the Nazis closed the Innsbruck Theological Faculty in 1939. It was late winter, pearl gray, and the view down into the valley of the Inn River was as beautiful as it must have been when Kaiser Maximilian hunted from the castle. Karl was visibly tired but insisted on driving on to Schwaz before we went on to Lans for supper. Schwaz had been an important center of mining, and a number of imposing buildings bear witness to its former prosperity. In the early 16th-century Franciscan cloister, the frescos of the life of Christ had just been restored. One scene, though hard to make out, impressed me especially. Finally I realized that it was the Lord “descending into hell to save the souls of the dead.” “No, no,” Karl corrected me, “their bodies!” But I remember still better another moment from the gathering shadows of that evening. Karl wanted to show me the Church of Mary with its unusual double nave: one for the nobility and the bourgeoisie, the other for the miners. While his typical interest in revealing historical detail impressed me, I was still more struck by something he did as we walked through the darkening north nave. Stopping at a painting of the Virgin and Child before which dozens of votive candles burned, he took a coin from his wallet and added a light. I began to do the same, but he stopped me and said, “No, one light is enough.” Yes, indeed, great theologian, holy priest, servant of the Lord and his church, dear friend, you were truly light enough for us all. Jesuit Fr. Leo O’Donovan is president emeritus of Georgetown University and visiting professor of theology at Fordham University.

National Catholic Reporter, March 26, 2004 |