Issue Date: May 16, 2003

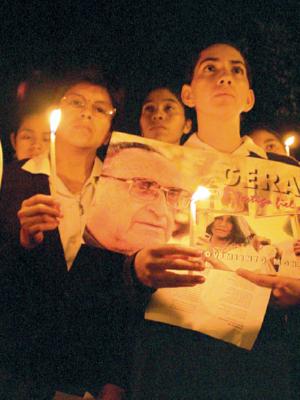

By PAUL JEFFREY When the followers of Bishop Juan Gerardi gathered April 26 with candles and songs outside the parish residence where the human rights champion was brutally murdered five years ago, the atmosphere had subtly changed in comparison to anniversaries past. Though a deep sense of loss still remained, gone was the feeling of mourning. As hundreds of people clapped and danced to lively music about Latin America’s martyrs, in place of mourning emerged a new sense of determination to take up again the cause for which Gerardi lived and died. Two days before he was killed, Gerardi made public Guatemala: Nunca Mas! -- the church-sponsored report on the violence that ripped apart this Central American country for more than three decades. He promised that the next step would be the church’s unconditional support for “the demands of the victims.” That proved unacceptable to this country’s patrons of violence, and so the bishop was swiftly eliminated. The project he had designed to reweave the social fabric of Guatemalan society, substituting truth for unrestrained terror, was put on hold. That was likely the intent of the bishop’s killers, and, until now, they have mostly succeeded. “Killing Gerardi was a tactic that worked,” said Fernando Suazo, an anthropologist who worked closely with Gerardi in the Interdiocesan Project to Recover the Historic Memory, known here as REMHI. “It effectively demobilized Gerardi’s vision. There remained people in each of the dioceses who wanted to continue with REMHI, but the knot that brought them all together was Gerardi the person. Without him the whole thing unraveled.”

Bishop Mario Rios Montt took over as head of the Archdiocesan Human Rights Office, which Gerardi had founded with a crusading group of young activists. While Rios remained committed to the human rights cause, he brought a more clerical posture that over time left lay staff frustrated at their reduced power to craft policy and make decisions. The rights office and the archdiocesan social ministry staff chafed under the new control by clergy and religious. Many of the most competent left. Many also viewed Rome’s appointment of Bishop Rodolfo Quezada of Santa Cruz del Quiché to replace Archbishop Próspero Penados when the latter retired in 2001 as a tempering of the archdiocese’s social activism. Quezada quickly backed away from social activism and changed the tenor of archdiocesan life. “With Penados, anyone could walk in the door of the archdiocese,” a longtime staffer told this writer. “But under Quezada it’s like a corporate headquarters, and only the cream of the society dares to come in.” In the rights office, whose scrappy staff was deeply involved with REMHI, almost all energy now focused on finding out who killed Gerardi. The task of “returning REMHI to the people” -- discussing the report in countless rural villages, providing legal and psychological support, exhuming mass graves, designing ceremonies for dealing with the disappeared, all steps toward justice and reconciliation -- was postponed. Tens of thousands of hours that would have been devoted to investigating and bringing to justice those who sponsored and carried out the war’s massacres -- what Gerardi had planned to do next -- were instead devoted to unraveling the complicated puzzle of who killed the bishop.

Deciphering that crime wasn’t an easy task to begin with, and it got tougher over the months as nine witnesses were killed and six witnesses, two prosecutors and a judge fled into exile. The quest for truth was often sidetracked by soap-operatic scenarios, like the determination by a visiting Spanish forensic expert that Baloo, the parish dog, was really the killer, having acted on orders shouted in German by Fr. Mario Orantes, who lived in the house with Gerardi. Baloo’s imprisonment kept people distracted from the real issue -- who killed Gerardi -- and what many would argue was even more important: the project that Gerardi had died for. Even though a three-judge panel convicted three military officers and Orantes of involvement in the killing in 2001, its request that prosecutors investigate at least 13 other people has gone unheeded. As long as the convictions remain under appeal, a process that could take years, the case is unlikely to go any further. “The judicial process … has been characterized more by a desire to obstruct the process than to search for the truth,” Quezada charged during a memorial Mass April 26. Yet some of Gerardi’s closest collaborators think the slain bishop’s dream may be deferred no longer. “Although it has taken some time, a new ingredient has slowly emerged, and in several dioceses the effort is getting started again either with the church or with nongovernmental organizations,” Suazo, the anthropologist, told NCR. “This new factor is Gerardi the martyr, which may end up as a stronger motivating factor than the living Gerardi. A martyr is a stronger force than a living leader. Gerardi dead is more powerful than Gerardi alive.” María Estela Pérez, a Kakchiquel Maya activist who has labored away on REMHI in the Sololá diocese, an almost clandestine effort given the opposition of two successive bishops, fondly recalls the day Gerardi presented the project’s final report in the capital’s metropolitan cathedral. “It went beyond joy. For the first time so many women and men had their own history in their hands, a history that their children could read tomorrow,” she told NCR. “And then they killed him, and we didn’t think we would have the strength to carry on the struggle. We also got distracted from what we had originally planned to do,” she said. Perez said the 2001 assassination of Charity Sr. Barbara Ann Ford and the 2002 torching of REMHI-related files in the Catholic church in Nebaj, both crimes that remain unsolved, were among the many setbacks to the task of implementing REMHI. “Yet we found moments of grace. When we gathered together we focused on the memory of Monseñor [Gerardi], and we found it impossible to talk of Monseñor without talking of the victims. I think it was his strength and spirit and inspiration that kept us focused on the victims, despite all the challenges.” In the San Marcos diocese, Bishop Alvaro Ramazzini reports that the process of returning REMHI to the people is just now getting started. The diocese had problems getting funding for the project, and also had to wrestle with archdiocesan bureaucrats in the capital to obtain the records pertaining to the highland diocese, which borders on Mexico. The diocese is now preparing a “popular version” of the report for workshops in indigenous villages.

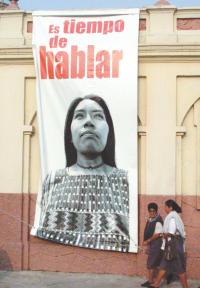

Ramazzini said Gerardi’s legacy has grown more consequential over time. “The strategy of the killers clearly backfired. If they had not killed Monseñor Gerardi, REMHI wouldn’t have the resonance it does today, five years later. By killing him, the assassins ultimately strengthened REMHI,” he told NCR. According to Cirilo Santamaría, a Carmelite priest and REMHI veteran who coordinates social ministries in the remote Peten region, Gerardi’s legacy continues to challenge the church to reach past its institutional boundaries to encounter the least of its sisters and brothers. “Gerardi was a bishop who went beyond the frontiers of the church. He was a bishop who incarnated himself, who knew how to walk with the poor, listen to the indigenous, who knew the way down into the gullies where the urban poor live, who attended to the victims without asking them their religion. The victims were simply people, and Gerardi embraced them where they were,” he told an April 25 public forum on Gerardi’s legacy. Santamaría, who also teaches theology at Guatemala City’s Jesuit-run Rafael Landivar University and helps coordinate the Monseñor Gerardi School of Theology and Ministry, a Saturday study program for lay activists, encouraged Gerardi’s followers to pick up where the bishop left off. “Gerardi wanted this country to break out from the years of fear and death that have reduced the majority of Guatemalans to silence. That’s why we’re today starting to continue the task he began, to recover our memory so that history won’t repeat itself. All of us are learning to shout together, ‘Never Again!’ Never again violence, never again massacres, never again assassinations.” Paul Jeffrey is a freelance writer who lives in Honduras. National Catholic Reporter, May 16, 2003 |